In this post, I present a concise account of the history of yoga according to Georg Feuerstein, as well as some annotations that problematize or complicate it.

The history of yoga according to Feuerstein

The German scholar argues that the earliest conclusive evidence of proto-yogic ideas and practices is found in the Ṛg Veda hymns, regarded as revealed knowledge by Hindu orthodoxy (Feuerstein, 101). These hymns may have been composed as early as the fifth millennium BCE, and reflect some features of the proto-yoga of these sages (ṛṣis): concentration, regulation of the breath during recitation, devotional invocation, surrendering the ego, and visionary experience (97). Esoteric knowledge of proto-yoga might also be found in hymns collected some centuries later in the Atharva Veda (114-5). The nomadic vrātya brotherhoods mentioned in these hymns appear to have been involved in the early developments of yoga on the fringes of Vedic society, perhaps even anticipating tantric and nondualist ideas (119-23).

The next milestone in the history of Yoga involved an “active interpretation and reinterpretation of the Vedic heritage”, reflected in the Brāhmanas, Āranyakas, and Upaniṣads. This period would be marked by the emphasis on direct experience of the Divine through asceticism and meditation (or “inner worship”, upāsana), in relative contrast to sacrificial ritualism (126). According to Feuerstein, this esoteric wisdom rooted in asceticism is a fuller articulation of an older doctrine of the transcendental Self (hence the designation of Vedānta, end of the Vedas) (127). Among other important Upaniṣads, the Katha Upaniṣad (c. 1000 BCE) is a very influential work that explicitly deals with yoga as a process for stabilizing the mind and reversing the unfolding of the world in consciousness (134-136) (see critical discussion below).

Outside the Vedic fold, two yoga traditions merit special attention: Jainism and Buddhism. Jainism is a non-vedic Śramaṇa (ascetic) tradition founded by Vardhamāna Mahāvīra around 500 BCE (139), whose teachings stress the concepts of tapas (austerities) and a strict ethics code (139, 148). A contemporaneous historical figure was Siddharta Gautama, who gave birth to Buddhism and a whole variety of yoga traditions (155).

The following period is the “Epic Age”, best represented by the Rāmāyana and the Mahābhārata (183). The earliest surviving text of Vaiṣnavism is the Bhagavad Gītā, a section of the Mahābhārata famous for integrating karma, jñāna, and especially bhakti yoga ideas (187-91). Feuerstein argues that the present form of this work is approximately 2,500 years old (279). The Vaiṣnava traditions developed their own nondualist approach to yoga, codified in the samhitās in the early centuries of the common era (279). The devotional aspect (bhakti) is particularly evident in later texts such as the Bhāgavata Purāṇa (c. 10th century CE) and in medieval accounts (282, 291).

The Yoga Sūtra of Patañjali (c. 2nd century CE) is “the climax of a long development of yogic technology”, even though it appears to be a systematization instead of a truly original work (214-6). Patañjali shaped yoga into a “classical format” or “authoritative system” (darśana) different to nondualism (213-5). Several centuries later, Śankara (c. 700 CE) founded Advaita Vedānta, an influential school rooted in the nondual teachings of the Upaniṣads (213, 312).

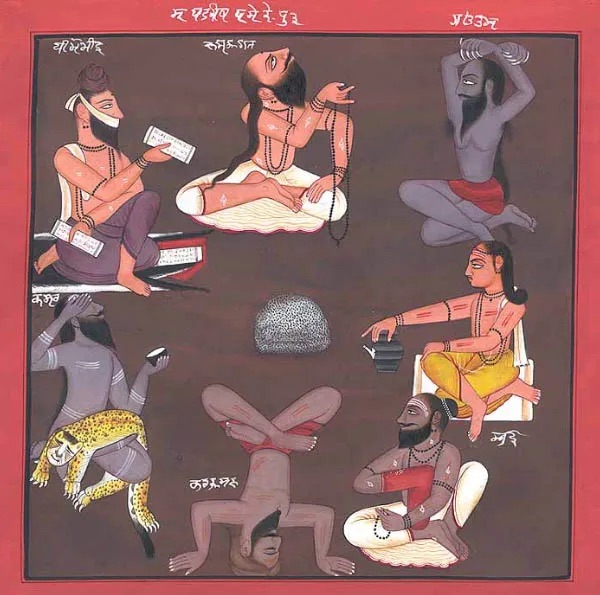

Among the most important “Post-Classical” Śaiva texts (c. 7th-17th centuries CE) are the āgamas, composed in both orthodox “right-hand” settings and transgressive “left-hand” sects (257-269, 296-9). Texts known as tantras (c. 500 CE onwards) emphasized the feminine Śakti aspect of a nondual metaphysics, and their teachings appealed to a wider audience (264, 342-4). Tantric practices aimed at gaining knowledge of the ultimate Reality in all aspects of conditioned existence (343). Many ideas about the subtle body stem from the tantra and haṭha yoga of the Siddhas (8th-12th centuries CE) and the Nāths (9th century CE onwards) (350, 353). The tantric path found in haṭha yoga has the sole aim of uniting Śakti and Śiva, a transformative process that takes place in and through the body (357, 382) (see critical discussion below). The Haṭha Pradīpikā is a very influential text of haṭha yoga composed in the middle of the 15th century CE by Svātmārāma (423).

Against a monolithic, continuous development: some critical annotations

The idea of the internal sacrifice is found in verse 2.5 of the Kaushītaki Upaniṣad, where it is presented as taking place inside the body and mind of the practitioner, as opposed to the orthodox sacrificial fire of the Brahmins. Is this idea of internal sacrifice the original meaning of sacrifice (yajña) in the Ṛg Veda? Feuerstein favors a symbolic interpretation of the sacrificial ritualism of Ṛg Veda, in line with later ideas found in the later Upaniṣads (105). In this sense, the teachings of the Upaniṣads would be another step in the progressive revelation of the symbolism and metaphoric language of earlier Vedic texts. Allusions to the inner world (microcosm), more clearly reflected in the later Upaniṣads, could be couched in this dense symbolism.

However, there are reasons to consider the possibility of this process being a radical shift in South Asian spiritual thought, or to at least acknowledge some degree of discontinuity in the Vedic tradition. The issue of dating ancient texts is still surrounded by much debate. For instance, while Feuerstein suggests that the Katha Upaniṣad might have been written as far as 1000 BCE (134), Andrea Jain dates this work to approximately the 3rd century BCE (8). This speaks in favor of a cautious approach towards some of the more extraordinary claims of continuity. Panikkar takes the middle road and explains that even though the conception of sacrifice seems to have changed over time, the basic idea of creative action has persisted (347).

Claims of continuity are also found in the field of modern yoga. Feuerstein mentions Krishnamacharya, who traced his lineage to the Vaiṣṇava bhakti preceptor Nāthamuni (c. 10th century CE). Andrea Jain has studied such claims in modern postural yoga, and advocates framing the debate not in terms of “authenticity”, but in terms of the “collective and divergent meanings and functions their practitioners attribute to them” (173).

Feuerstein stresses the importance of the Siddhas (8th-12th centuries CE) and the Nāths (9th century CE onwards) in the origins of haṭha yoga. Although Mallinson acknowledges he once held the common scholarly view of haṭha yoga as a Nāth reformation of tantric practices, he now questions this thesis (2016, 111). Mallinson shows that the origins of haṭha yoga might be found in more-or-less sectarian Śaiva, Vaiṣṇava, Śākta and even Buddhist milieux (2016, 110-117). In his view, many texts of haṭha yoga are notorious for being explicitly anti-sectarian, perhaps marking a trend of democratization of these practices also among householders (Mallinson 2016, 122).

Feuerstein claims that the tantric path found in haṭha yoga has the sole aim of uniting Śakti and Śiva, a transformative process that takes place in and through the body (357, 382-90). In contrast, Mallinson identifies two paradigms: (a) the preservation of bindu; and (b) the rise of the kuṇḍalinī through the suṣumnā. The original logic at play in the earliest formulations of hatḥa yoga would have been that of raising and conserving the semen (bindu) in men (the feminine rajas was sometimes mentioned) (2011, 770). The aim of this process was to avoid the dripping of the life essence from its reservoir in the head, believed to be the cause of weakness and death due to its expenditure in the solar fire at the base of the central channel (Mallinson 2016, 111). Mallinson explains that modern ascetic orders such as the Daśanāmī saṃnyāsīs and the Rāmānandīs have preserved some aspects of this relatively orthodox tradition (2011, 779). In later formulations of hatḥa yoga, we find a second superimposed somatic logic: kuṇḍalinī energy rises through the central channel (suṣumnā) and reaches a reservoir of the nectar of immortality (amṛta) in the head, which floods bestowing rejuvenation and immortality (Mallinson 2011, p. 770). This second logic appears to be connected to the practice of laya yoga and the Paścimāmnāya lineage of Kaula Śaivism (Mallinson 2011, 774).

Bibliography

Feuerstein, Georg. 2008. The Yoga Tradition: Its History, Literature, Philosophy and Practice. Hohm Press.

Jain, Andrea. 2015. Selling Yoga. Oxford University Press.

Mallinson, James. 2011. “Haṭha Yoga” in Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, vol. 3. Ed. Knut A. Jacobsen et al. Leiden: Brill, 2011. pp. 770-781.

______________. 2016. “Śaktism and Haṭha Yoga” in Goddess Traditions in Tantric Hinduism: History, Practice and Doctrine, Ed. Bjarne Wernicke Olesen. London: Routledge, pp. 109-140.

Panikkar, Raimundo. 1977. The Vedic experience: Mantramañjarī . University of California Press.

Leave a comment