Introduction

My interest in undertaking this research arose from a specific practice taught in the Haṭhapradīpikā (HP) under the name nādānusandhāna, which involves actively listening to internal sound (nāda) as a means for attaining a state of dissolution or absorption (laya). My initial intention was to do a comparative study of primary texts to shed light on the practice of listening to inner sound as a tool for psychospiritual transformation in traditional yoga and tantra.

Through my research, I have been able to approach the following general questions regarding several primary sources: (i) How is the concept of nāda understood? (ii) Which concrete practices are taught to perceive the inner sound? And (iii) Are there any notions about the subtle body that serve as practical or explanatory frameworks for said practices?

However, when the time came to present the results of my research in a limited amount of space, the sheer amount of material I had gathered and the complexity of the topic forced me to be less ambitious. In an effort to present some partial results of my research in a way that still preserves the spirit of my original purpose, I decided to structure this paper as follows: (i) First, I provide some context on the sacred nature of sound in traditional South Asian yoga and tantra, exploring the possible origins of the practices of listening to internal sound; (ii) I then delve into the study of the HP as perhaps the most well-known traditional text that teaches such practices; (iii) Lastly, I extract some general conclusions.

I. Sacred nature of sound in traditional South Asian yoga and tantra: nāda, bindu and laya

In this chapter, I present a brief overview of the understanding of sound in premodern yoga and tantra. In doing this I provide a foundation of three key concepts for the study of the HP: nāda, bindu, and laya. A note of warning is justified before attempting to define these concepts: it is important to avoid considering these provisional definitions as valid in all circumstances. This is especially true since words are frequently used in different senses and often carry symbolical weight.

Monier-Williams Sanskrit dictionary indicates that the word nāda comes from the verbal root √nad. The first three definitions provided express a general feeling of the meaning of the term: (i) “a loud sound, roaring, bellowing, crying” (in the Ṛg Veda); (ii) “any sound or tone” (in grammatical works known as the prātiśākhyas, and the Rāmāyaṇa); and (iii) “(in the Yoga) the nasal sound represented by a semicircle and used as an abbreviation in mystical words” (Bhāgavata Purāṇa). It is worth noting that there is no qualification of the sound as necessarily being internal.

A much larger list of definitions is given by Monier-Williams in the entry for the word bindu, for which no verbal root is indicated (the online Dictionnaire Héritage du Sanscrit does not identify one either). Some relevant definitions are: (i) “a detached particle, drop, globule, dot, spot” (in the Atharva-Veda); (ii) “the dot over a letter representing the Anusvāra (supposed to be connected with Śiva and of great mystical importance)” (in the Mahābhārata; the collection of tales known as the Kathāsaritsāgara; andthe Bhāgavata Purāṇa). It is worth noting that Monier-Williams does not make a specific reference to semen. Mallinson believes that this interpretation is an original innovation of the Amṛtasiddhi, an early haṭha yogic text that prescribes the preservation of bindu as essential for liberation (2016b, 5).

For the word laya, Monier-Williams gives 18 definitions. I have selected five that can provide a good idea of its meaning in relation to the previous two concepts: (i) “melting, dissolution, disappearance or absorption in” (in the Upaniṣads); (ii) “rest, repose” (in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa and the epic poem Śiśupāla-vadha): (iii) “mental inactivity, spiritual indifference” (in the Vedāntasāra); (iv) “making the mind inactive or indifferent” (in the Bhāgavata Purāṇa). Monier-Williams does not mention the root √lī, associated to the word laya in the Dictionnaire Héritage du Sanscrit. This dictionary gives the following information for the root the root √lī: “to erase oneself, to disappear, to be absorbed; to lie down, to hide oneself” and defines laya as: “absorption into, attachment to; disappearance, dissolution, death; end of the world”.

Having reviewed the definitions given in the lexicon, I now take a closer look at the concepts of nāda and bindu, which lead to the idea of laya. Beck attempts to elucidate the meaning of the terms nāda and bindu in his book Sonic Theology. Beck notes that, in addition to the definitions given in the dictionary, the ideas of “reverberation,” “resonance,” and “sonant” are also associated with the generic word nāda (81). Moreover, when referring to the relationship between the concepts of nāda and bindu, Beckexplains that these two ideas are almost always associated in the context of Śiva-Sakti metaphysics (81). More specifically, Beck mentions the expression candra–bindu, which he explains as “symbolic combination of nāda as semicircle (candra, or half-moon) with bindu, as dot” (81-82). A further reference to Sanskrit linguistics helps clarify the meaning of these two concepts: nāda is commonly associated with the anusvāra, which is the nasal after-sound, symbolized by a dot (Beck, 82). Beck then concludes that in nāda-yoga and related Tantric traditions, nāda means the reverberating sound, particularly the “buzzing nasal sound with which the word AUM fades away,” leading to bindu, “the nasal point of the anusvāra” (82).

The previous remarks are helpful in understanding the close relationship between nāda and bindu, but nothing has been yet said about the manifestations of these concepts in the specific context of premodern South Asian spiritual yogic and tantric practices. Commenting on some verses of the Yoga-Sūtra, which deal with the recitation of, and meditation on, the sacred syllable Om, Beck states that the practice of yoga “reflects an ongoing concern with the use of sacred sound and linguistic symbols as fundamental aids in meditation” (85). Beck sees in the practice advocated by Patañjali an important antecedent of techniques of meditation on sacred sound that arose later (85). To justify this assertion, Beck explains that Vācaspati (c. 10th century C.E.), an influential scholar who expounded on Vyāsa’s commentary on the Yoga-Sūtra, seems to have made the earliest reference to nāda in the classical yoga tradition, in a sense that transcended the meaning of phonetical voiced sound associated to Mīmāmsā and grammar (89). In a gloss to Vyāsa’s commentary, Vācaspati uses the components of the syllable AUM as a framework to explain a practice that involves control of the breath and concentration on inner light present in certain locations of the subtle body (Beck, 89, 91).

Beck ties these ideas to earlier elements found in the Maitri and the Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣads, to explain how a distinctly yogic understanding of sacred sound seems to have arisen in contrast to the nondual Vedāntic conception (89-90). From the perspective of Advaita-Vedānta, the Supreme Brahman, equated to the fourth state (turīya), is beyond sound, and all sounds finally merge into soundlessness (Beck, 90-91). In contrast, Vācaspati appears to identify the highest state with Nāda-Brahman, which is not devoid of sound (Beck, 91). Beck notes: “The Maitri-Upaniṣad, being one of the principal Upaniṣads as well as a philosophic source for Advaita-Vedānta, has been singularly cited as being of a formative nature with regard to the subject of Nāda-Yoga, or the Yoga technique of meditation on sacred sound (…). Indeed, by taking a possible cue form verse 6.22 of this text, the “hearing of divine sounds” has been emphasized in the Yoga-Upaniṣads, the principal Haṭha-Yoga texts, and by the Nāth Yogīs (followers of Gorakhnāth). The common sharing of “mystical audition” among these traditions indicates a fertile area for investigation.” (92). I would like to emphasize the centrality of this issue, since this theme will be explored again in the next chapter.

Beck is rightly cautious when he warns that none of the commentaries of the Yoga-Sūtra can be said to represent the entirety of the Yoga philosophy, nor univocally reflect the concrete practices (91). In addition, it is worth noting that the Yoga-Sūtra most probably predated Vācaspati’swork by several centuries; Beck even believes them to be separated in time by more than a thousand years (83, 85). Therefore, I believe it would be wise to be cautious when drawing conclusions about the relationship between the three links to which Beck refers: (i) the practice advocated by Vācaspatiin his commentary on Vyāsa’s Bhāṣya; (ii) Vyāsa’s gloss on the Yoga-Sūtra; and (iii) Patañjali’sown allusions to the sacred syllable Om. Nevertheless, the previous remarks should be enough to provide a very basic context of at least one early reference (circa 10th century C.E.) to sacred sound as an object of yogic spiritual practice.

Leaving aside the hermeneutical analysis of the references to sound in the Yoga-Sūtra, I have found throughout my research that mainly three groups of traditional texts have been identified by scholars as representative of the use of internal sound as an object of spiritual practice: (i) the Yoga-Upaniṣads; (ii) some Śaiva Tantras; and (iii) what could be loosely termed as texts of “traditional haṭha yoga.”I will now refer to each of them as I explore the topic of the origins of these techniques and reveal how they are tied to the third key concept, laya.

What are the Yoga-Upaniṣads and what is their place in the context of the three groups of texts subject of my analysis? The title of this paper comes from the work of Eliade on the Nādabindu Upaniṣad, one of the most representatives of the Yoga-Upaniṣads. Eliade believed that this text was composed in “a yogic circle that specialized in ‘mystical auditions’ – that is, in obtaining ‘ecstasy’ through concentration on sounds” through the application of specific techniques that sought to “transform the whole cosmos into a vast, sonorous theophany” (133). Varenne wrote that “Although the first Tantras and Yoga-Upaniṣads date from the 8th century after Christ, we may and should assume as a certainty that their contents were formulated at least ten centuries earlier, then continuously elaborated upon and renewed before being finally fixed in the texts we possess” (Beck, 92). Although this might be true of the “raw material” of the practices themselves, Bouy has documented in great detail how almost all of the so-called Yoga-Upaniṣads are in fact the crystallization of the Advaitin interest in non-orthodox haṭha yoga practices. Bouy meticulously dissects the Yoga-Upaniṣads and describes how, probably around the first half of the 18th century, at least nine of them were either enlarged or wholly assembled drawing from earlier haṭha yogatexts (115-116).

However, it seems to me that Bouy might have been mistaken in believing that the haṭha yogatechniques that ended up in the Yoga-Upaniṣads had originated in a Nāth milieu (116). It is now known, through the exceptional scholarly work carried out by Mallinson, that these practices were probably techniques that arose in a rather heterogeneous ascetic setting and were at a later point co-opted by the Nāths (2016a, 123). I am not discussing these works in greater detail, since they seem to postdate the two other groups of texts that deal with our subject matter. However, I would like to advance one general conclusion of this paper at this point, using an example from the Yoga-Upaniṣads. Beck points out some discrepancies between some of these texts regarding certain matters (94-96). For instance, The Yogaśikha-Upaniṣad (which borrows significantly from the Yogabīja according to Bouy, 104) states that the origin of nāda is the Mūlādhāra cakra, whereas the Darśana-Upaniṣad (not analyzed in detail by Bouy) locates the source in the top of the head, in the Brahmarandhra (as also does the Gorakṣapaddhati). I will later present further proof evincing that it is not possible to postulate the existence of an entirely coherent conception of internal sound in premodern South Asian spiritual practice.

With the previous considerations in mind, I now turn to the Śaiva Tantras before studying traditional haṭha yoga. Mallinson believes that the practice of listening to internal sound, called Nādānusandhāna in the HP, is found in some formulations of yoga that predate what is now known as traditional haṭha yoga, and references the work of Vasudeva on the Mālinīvijayottaratantra (2011, 775). This monograph includes not only atranslation of some chapters of this voluminous text, but also an excellent commentary accompanied by cross-references to other Śaiva Tantras. I will use this work as my source for the following very general remarks, since this is an extremely complex field of study and my understanding of it is still quite limited.

What is the Mālinīvijayottaratantra, and how does it fit into the overall picture that I have been painting? Despite having done extensive work on this text, Vasudeva believes that “it is still not possible to accurately place or date the Mālinīvijayottaratantra original compilation” (146). In my limited research, I have not been able to find a date for the composition of this text, but I will at least suggest that its terminus ad quem is marked by Abhinavagupta’s lifetime (c. 975–1025 C.E., according to Sanderson, 54). I base this assertion on Vasudeva, who stated that Abhinavagupta made the Mālinīvijayottaratantra “the linchpin for his synthesis of Trika and Krama elements into a householders’ religion” (146). According to Vasudeva, this text “presents not a single yoga but attempts to integrate a whole plethora of competing yogic systems” (11). In general, it could be described as a “Tantra of the Trika division of Śaiva revelation” (Vasudeva, 5), a tradition in which the concept of laya occupies a central place (Mallinson 2016a, 129), as I will now show.

In order to understand the conception of internal sound in these Śaiva Tantras, it is essential to clarify the term lakṣyabheda (sometimes appearing as lakṣya). This expression can be defined as a reference to various manifestations of the formless Śiva “that serve as teleological magnets” for the practitioner to focus in his quest for the “conquest of realities” (Vasudeva, 255), be it liberation or the attainment of supernatural siddhis (253). The number of lakṣyas varies, but several Śaiva Tantras mention sound as one of them. However, different terminology is sometimes used, for which I give three examples from each of the following texts: the Mālinīvijayottaratantra, the Dīkṣottara, and the Svāyambhuvasūtrasaṅgraha.

In the Dīkṣottara, the word used is not nāda but śabda (Vasudeva, 277). Monier Williams gives several definitions for this word, two of which I find of particular relevance: (i) “sound, noise, voice, tone, note;” and (ii) “the sacred syllable Om.” Curiously, these two definitions of a term found in the Śaiva Tantras are linked by Monier Williams to two of the Yoga Upaniṣads (referred to earlier): the Dhyānabindu and Amṛtabindu Upaniṣads, respectively. The second example of terminological variance comes from the Mālinīvijayottaratantra, where the word used is dhvani (Vasudeva, 256). Two of the definitions given by Monier Williams are: (i) “sound, echo, noise, voice, tone, tune, thunder” (from the Atharva-Veda); and the more mysterious (ii) “empty sound without reality” (for which no source is given). The third example I will give comes from the Svāyambhuvasūtrasaṅgraha, where the term employed is nāda (Vasudeva, 258).

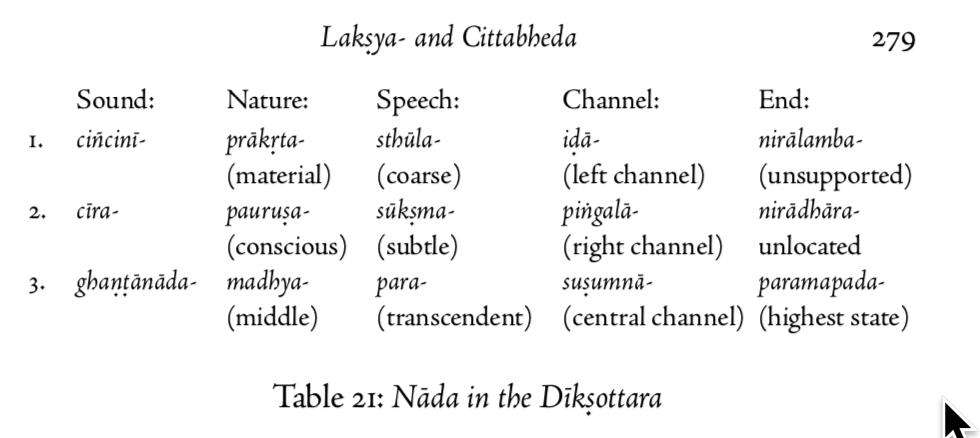

Irrespective of the term used, the truth is that several Śaiva Tantras give advice on how to merge (layaṃ) into this internal sound or resonance (Vasudeva, 273-278). Moreover, the texts that propound a system of six lakṣyas texts seem to largely agree that contemplation on sound “leads to isolation and liberation” (Vasudeva, 260-261). Intricate associations between types of sounds, components of the subtle body, and stages of spiritual attainment are explained, but this is not the place to go over them in detail. I would only like to give one example of particular interest before proceeding to the study of traditional haṭha yoga. Earlier, I emphasized Beck’s discussion of the contrasting notions of the Ultimate being soundless or not. I would like to go over this idea again because there is a curious expression in some of these Śaiva Tantras that is also related to this topic. In the Dīkṣottara, three different sounds (ciñcinī, cīra, and ghaṇṭānāda) are associated to the threefold nature of man (prākṛta, pauruṣa, and madhya) three progressively subtler “levels of speech” (sthūla, sūkṣma and para), the three main nadīs (iḍā, piṅgalā and suṣumnā), and three spiritual states (nirālamba, nirādhāra and paramapada) (Vasudeva, 278-279). I will not discuss these terms in detail; I would only like to draw attention to the fact that the sound of the reverberation of a bell (ghaṇṭānāda), associated to the central channel and the third stage (paramapada), is said to gradually fade as it leads to the silent fourth state (Vasudeva, 279). The term nādānta (nāda + anta: lit. end of sound) in the context of a mantra practice called uccāra (Vasudeva, 279, 284-286), seems to me to allude to this same state.

I have thus far reviewed two main groups of texts that deal with my subject matter. In doing so I have provided more elements to better understand the three key terms (nāda, bindu and laya) and explored the possible origins of the use of internal sound as an object for concentration in premodern South Asia. Now, how does traditional haṭha yoga fit into the whole frame of spiritual traditions that I have been discussing? Is there a link between the Śaiva Tantras and the techniques of this third group of texts?

According to Mallinson, nāda is tied to haṭha yoga from its earliest definition in a buddhist text,Puṇḍarīka’s eleventh-century Vimalaprabhā commentary on the Kāla-cakratantra: “haṭhayoga is said to bring about the ‘unchanging moment’ (akṣarakṣaṇa) ‘through the practice of nāda by forcefully making the breath enter the central channel and through restraining the bindu of the bodhicitta in the vajra of the lotus of wisdom’” (2016a, 110). The sense of the terms nāda and bindu here is unclear; it is not explained by Mallinson, nor was I able to find a full version of this text that might have helped me elucidate this matter. This is evidence, however, of the close relationship between these two key concepts, as well as being proof of the relevance of these elements in spiritual practice.

For reasons of space, I am not able to present here a comparative study of the primary texts of haṭha yoga as pertains to their use of internal sound as an object for concentration. I will now fast-forward to the HP, which is perhaps the most representative text of traditional haṭha yoga. In the next chapter, I will discuss the practice of nādānusandhāna as a paradigm of sorts of the practices of concentration of internal sound in traditional haṭha yoga. I will also briefly speculate about a possible link to the earlier Śaiva Tantras that I have been discussing, including a few discrete references to a few other primary haṭha yoga texts.

II. Nādānusandhāna in the Haṭhapradīpikā

The HP is a classic text composed circa 1450 C.E., stands out for being the first text that explicitly “sets out to teach hatḥa yoga above other methods of yoga” (Mallinson 2011, 771-772). It is undoubtedly the locus classicus of haṭha yoga, even though it is “essentially a compilation, a work of synthesis made up of verses borrowed from yogic (and para-yogic) literature” (Bouy, 9). Mallinson identified a “Corpus of early haṭha yoga,” which he contrasts to what he terms the “more catholic ‘classical’ haṭhayoga of the HP and subsequent works” (2016a, 111). Indeed, most of the contents that later went into the composition of the HP are found in the eight works that make up the ‘Corpus of early haṭha yoga’: Amṛtasiddhi, Dattātreyayogaśāstra, Gorakṣaśataka, Vivekamārtaṇḍa, Yogabīja, Khecarīvidyā, Amaraughaprabodha, Śivasaṃhitā (Shaktism, 5).

According to Mallinson, the HP “combines elements from a wide range of yogic teachings, but in essence comprises the gross physical techniques of an ancient extra-Vedic ascetic tradition overlaid with subtle visualisation-based Śaiva yoga” (2014, 226). While the earlier Śaiva texts were inextricably linked to secretive initiatory traditions, haṭha yogain a sense democratized these practices by detaching them from their sectarian origins, thus synthetizing Śaiva and Vedāntic nondualisms (Mallinson 2014, 236, 238). In a general sense, haṭha yoga allowed some of the practices of Śaivism to endure beyond its heyday (Mallinson 2014, 225).

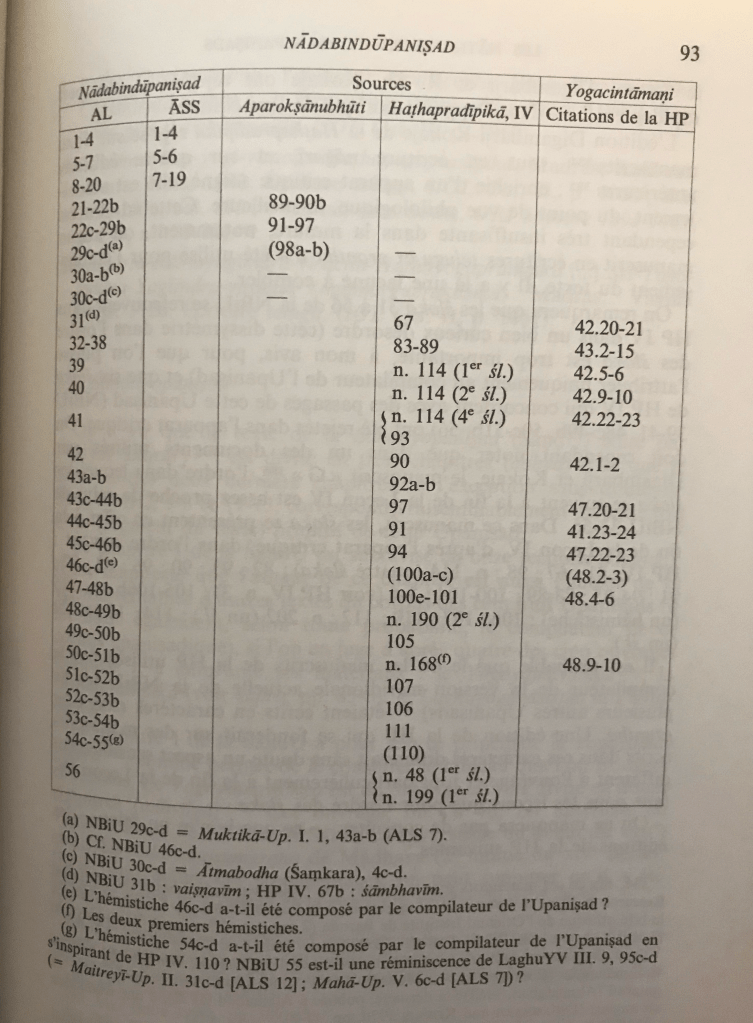

I relied on the work of Mallinson (in turn based on Bouy’s previous research) to identify the sources of the most important verses of the HP related to nāda and laya. Five texts of various origins surfaced: (i) Śivasaṃhitā (HP 1.43 from ŚS 5.47); (ii) Vivekamārtaṇḍa (HP 3.64 from VM 41, HP 4.6 from VM 162-163); (iii) Amanaska (HP 4.31-4.32 from AY 2.21-22); (iv) Kaulajñānanirṇaya (HP 4.33 from KJN 3.2c–3b); (v) Amaraughaprabodha (HP 4.69 from AP 45, HP 4.70–77 from AP 46–53); and (vi) Uttaragītā (HP 4.100 from UG 1.42).. Among these, the Śivasaṃhitā, the Vivekamārtaṇḍa, the Amanaska and the Uttaragītā blend elements of Vedānta and Śaiva nondualism, while the Kaulajñānanirṇaya and the Amaraughaprabodha are Śaiva texts (Mallinson 2014, 232, 235-236). However, Mallinson failed to identify the direct sources for the majority, and the most noteworthy verses of the HP that deal with the subject of nādānusandhāna (

verses 4.1, 4.28-30, 4.34, 4.65-68, 4.78-79, 4.80-99, 4.101-103, 4.105-106). They are either original verses or their direct source is still unknown.

The meaning of this paper’s three key concepts in the HP is not always clear, especially bindu. This word is used in the text in verses 3.42-43, 3.87-91, and 4.28, as a reference to semen, counseling its conservation. This is a definition that I did not find in the lexicon, and according to Mallinson it is an innovation of the Amṛtasiddhi that had an enduring influence (2016b, 5). An apparently different sense of the word bindu is found in verse 3.64, which is of particular interest since it associates the concepts of bindu and nāda. According to this verse, mūlabandha allows the practitioner to unite prāṇa and apāna, nāda and bindu, granting success in yoga. A third example, more enigmatic, is found in verse 3.100, which explains that in women who practice vajrolī mudrā, the nāda is transformed into “a certain kind of light” (bindutāmeva). This might be related to the Śaiva techniques of bindu lakṣya mentioned earlier, which seemed to involve concentration on inner light. However, this is still the context of vajrolī, a practice that does involve sexual fluids.

Another association between nāda and bindu is found in the rather abstruse verse 4.1, which reads: “Prostrations to the great Guru Lord Śiva who is of the nature of nāda-bindu-kalā (and) by constant devotion to whom the sādhaka attains the ultimate state”. The allusions to nāda, bindu and kalā as the nature of Śiva seem to me redolent of the Śaiva Tantra texts mentioned earlier. The sense of the word nāda in the text is clearly that of internal sound, but the interpretation of the terms bindu and kalā in the context of this verse presents some difficulties. I have already referred to ambiguity of the word bindu in the HP, so I now proceed examine the term kāla.

The sense of the word kāla in the context of verse 4.1 is unclear. Verses 3.40, 3.130, 4.13, 4.48-49, 4.103, 4.108 clearly seem to use it in the sense of time and/or the cycle of birth and death. On the other hand, a more cryptic use of the term is found in verse 4.17, where it is said that the suṣumna “swallows up this very time”, adding that “These are said to be mysterious secrets”. It could well mean that time is the nature of Śiva (i.e. Śiva is eternal). I suspect that there is a more esoteric meaning of the world kāla, perhaps related to the Śaiva lakṣyas, but I haven’t been able to uncover using the text of the HP itself.

So far I have discussed nāda and bindu, two of the three key concepts in the context of the HP. To understand how laya is associated in the HP to the practice of listening to internal sound, let me now clarify the words used to refer to the practice itself. In his commentary, Brahmānanda does give an explanation of the threefold nature of Śiva mentioned in verse 4.1., related to dimensions, or possibly layers, of sound. In the ten-chapter version of the HP, this verse appears as 7.1, followed by a note from the translator which says that nadā stands for “internally aroused sound”, bindu for “internally aroused light” and kalā for the “rich sensation felt all over the body”, three experiences that would indicate the development of prāṇic activity in the body. There is no indication of the source for this interpretation, but it might make sense within the framework of the Śaiva lakṣyas.

According to Monier Williams, the word anusaṃdhāna is made up of the prefixes anu and saṃ, plus the verbal root √dhā. Three meanings without specific sources are given: (i) “to explore, ascertain, inspect, plan, arrange”; (ii) to calm, compose, set in order; and (iii) “to aim at”. Another term used in the HP is nādopāsana. Several meanings are given for the word upāsana, among which I selected one that I found particularly relevant: “homage, adoration, worship” (from the Sarvadarśana-Saṃgraha and the Vedāntasāra).

I will now present a brief analysis of the actual practice of nādānusandhāna (or nādopāsana). According to verse 4.65 of the HP it was taught by Gorakṣa, but nothing is said about the Śaiva Tantra traditions. In any case, the close relationship of this practice to the concept of laya is revealed in verse 1.43, which states that nāda is the supreme laya (as does the Śivasamhitā in verse 5.47). Laya is a concept that is more associated with visualization-based practices of Śaiva/Śakta traditions, as opposed to the more physical practices of traditional haṭha yoga(such as the bandhas, asanas, etc., Mallinson 2014, 226). The HP does not distinguish between laya-yoga and haṭha-yoga, as earlier haṭha yogatexts did (such as the Dattātreyayogaśāstra, the Yogabīja, the Amaraughaprabodha and the Śivasaṃhitā), but instead includes laya in its systematization of haṭha yoga(Mallinson, 2016a 115-118). Indeed, verse 1.56 reads: “The Haṭhayoga practice should be done in the following order – First āsanas, followed by various types of kumbhakas, then mudrās, followed by nādānusandhāna”. According to Mallinson, this is the culmination of a process of amalgamation that began with the Vivekamārtaṇḍa (2016a, 117).

Now, how does one perceive the nāda according to the HP? The technique of nādānusandhāna (or nādopāsana) involves sealing the ears with the fingers, and listening attentively to a series of internal sounds, in order to reach a state of dissolution (mainly verses 4.65 to 4.106). The previous practices of concentration on nāda as tools for attaining a state of laya found in the Śaiva Tantras are perhaps more meditative in nature than the more physical techniques that are the hallmark of haṭha yoga. However, there is an interesting resemblance between the practice of Saṇmukhīkaraṇa taught in a Tantric text called the Svacchandatantra and the technique of nādānusandhāna found in the HP. The Saṇmukhīkaraṇa (“mudra” of the six orifices, since it involves sealing the eyes, nostrils and ears using the fingers) is taught in the Svacchandatantra as a practice for meditating on bindu (bindu lakṣya), and whilethe description is rather cryptical, it seems to involve concentration on light instead of sound (nāda lakṣya) (Vasudeva, 272, 277). Basically the same posture is taught in verse 4.68 of the HP under the name of nādānusandhāna, a technique of concentration on internal sound; however, I did not find any explicit allusions to internal light in the context of this practice.

I believe that I might have found a “missing link” between these two practices while doing my comparative study of several primary textsof haṭha yoga. Somewhat mysteriously, verse 6.17 of the Gheraṇḍasaṃhitā reads: “Between the eyebrows and above the mind is a light consisting of om. Meditate on it as joined with a ring of fire.” Is this evidence of some sort of fusion between the Śaiva bindu and nāda lakṣyas? At a first glance, this would a be strange because they are apparently quite distinct paths: while the attainment of liberation is promised by the nāda lakṣya, the practice of bindu lakṣya is said to grant the practitioner “sovereignity over the yogis” (Vasudeva, 273). Nevertheless, I would like to argue that this should not lead to the dismissal of a possible link between the two practices. My hypothesis is grounded on the previously explained concept of the lakṣyas, which are manifestations of the nondual formless Śiva.

Finally, regarding the topic of the ultimate state having the quality of sound or being soundless, the HP seems to suggest that absorption into sound ultimately leads to Paramātmā, which is beyond all of sound (verse 4.101). This is also consistent with the Śaiva concept of nādānta, which I explored in the previous chapter.

III. Conclusions

Internal sound is also referred to using terms different to nāda, such as dhvani and śabda. There is not a single understanding of the terms nāda, bindu and laya in the context of these practices. As is often the case when it comes to spiritual topics, the words are ambiguous, possibly containing several layers of meaning through the use of symbolism.Beck’s hypothesis regarding the origins of these practices, which sees precedents in the Maitri and the Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣads, as well as in the Yoga-Sūtra, are dubious.The origins of these practices sound are obscure, but it appears like the technique of nādānusandhāna taught in the HP is deeply influenced by the Śaiva Tantras. In turn, the Yoga Upaniṣads seem to have been composed in the most part by borrowing from traditional haṭha yoga texts.In the HP and the Śaiva Tantras, the Ultimate state appears to be considered to be beyond sound, which is consistent with the concept of the lakṣyas as being manifestations of the formless and nondual Śiva.

- Internal sound is also referred to using terms different to nāda, such as dhvani and śabda.

- There is no single understanding of the terms nāda, bindu and laya in the context of these practices. As is often the case when it comes to spiritual topics, the words are ambiguous, possibly containing several layers of meaning through the use of symbolism.

- Beck’s hypothesis regarding the origins of these practices, which sees precedents in the Maitri and the Māṇḍūkya Upaniṣads, as well as in the Yoga-Sūtra, are dubious.

- The origins of these practices sound are obscure, but it appears like the technique of nādānusandhāna taught in the HP is deeply influenced by the Śaiva Tantras. In turn, the Yoga Upaniṣads seem to have been composed in the most part by borrowing from traditional haṭha yogatexts.

- In the HP and the Śaiva Tantras, the Ultimate state appears to be considered to be beyond sound, which is consistent with the concept of the lakṣyas as being manifestations of the formless and nondual Śiva.

- Haṭha yoga, and particularly the HP, might have made it possible for some obscure Śaiva Tantric practices of listening to internal sound to survive beyond the heyday of Saivism and being democratized.

- The Śaiva Tantras probably contain clues for deciphering some of the hermeneutical problems posed by the HP and other traditional haṭha yogatexts.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beck, Guy L. Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. University of South Carolina Press, 1993.

Bouy, Christian. Les Nātha-Yogin et les Upaniṣads. Diffusion de Boccard, 1994.

Eliade, Mircea. Yoga: Immortality and Freedom. Princeton University Press, 2009.

Haṭhapradīpikā of Svātmārāma in: Maheshananda, Swami and B.R. Sharma. A Critical Edition of Jyotsnā. Kaivalyadhama, 2010.

Haṭhapradīpikā of Svātmārāma (10 chapters). M.L. Gharote and P. Devnath. Kaivalyadhama, 2017.

Mallinson, James, translator.(2004) Gheranda Samhita: the original Sanskrit and an English translation. Yoga Vidya, 2004.

Mallinson, James. (2011) “Haṭha Yoga” in Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, vol. 3. Ed. Knut A. Jacobsen et al. Brill, 2011. pp. 770-781.

______________. (2014) “Haṭhayoga’s Philosophy: A Fortuitous Union of Non-Dualities” in Journal of Indian Philosophy, vol. 42, Issue 1. Springer Netherlands, 2014, pp. 225-247.

______________. (2016a) “Śaktism and Haṭha Yoga” in Goddess Traditions in Tantric Hinduism: History, Practice and Doctrine, Ed. Bjarne Wernicke Olesen. Routledge, pp. 109-140.

______________. (2016b) “The Amṛtasiddhi: Haṭhayoga’s tantric Buddhist source text” draft of an article to be published in a festschrift for Professor Alexis Sanderson. Made available by the author on https://www.academia.edu/26700528/The_Am%E1%B9%9Btasiddhi_Ha%E1%B9%ADhayogas_Tantric_Buddhist_Source_Text

Sanderson, Alexis. “The Śaiva Age – The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period.” In Genesis and Development of Tantrism, Ed. Shingo Einoo. University of Tokyo, Institute of Oriental Culture, March 2009, pp. 41–349.

Vasudeva, Somadeva. The Yoga of the Mālinı̄vijayottara. Institut Français de Pondichéry, 2004.

Leave a comment