Para la traducción al español, haz click aquí.

Introduction

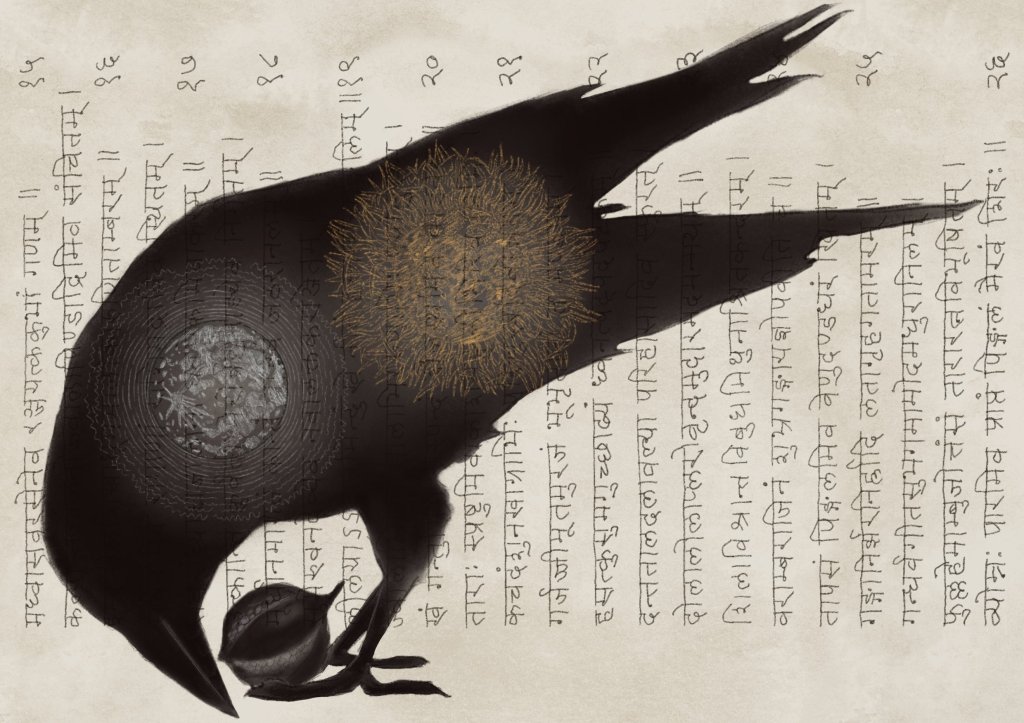

In this article, I argue that the story of Bhuśuṇḍa in the Yoga Vāsiṣṭha (YV) may inspire a multi-species ethics of compassion, embodied through contemplative practices that foster alternative views of self and freedom.

The YV is an extensive, multi-layered collection of stories that present teachings across religion and philosophy in poetic Sanskrit.[1] The primary narrative frame is a conversation between the sage Vasiṣṭha and his pupil Rāma, archetype of the ideal ruler and an incarnation (Skt. avatāra) of the Hindu deity Viṣṇu. Throughout its 62 tales, the text weaves strands of Indian philosophy: Advaita, Yogācāra Buddhism, and Trika or Kashmir Śaivism.[2] Although often attributed to Vālmīki, it is thought that the YV was probably compiled by several authors over a long period of time, reaching its present form about a millennium ago.[3] In chapters 14 to 28 of the YV’s Nirvāṇa section, Vasiṣṭha narrates his meeting with the mythical crow Bhuśuṇḍa.[4]

This article on a multi species ethics of compassion inspired by the tale of Bhuśuṇḍa is structured as follows. In the first section, I point out some intersecting crises of Westernized Modernity that will lay the foundation of my argument in terms of relevance. Next, I offer a concise explanation of some doctrines of Buddhism that inform my reading of the YV story. In the third section, I summarize the tale of Bhuśuṇḍa, closely examining its metaphysical and ethical teachings, as well as the contemplative practices that ground them. Finally, I extract some conclusions based on a reading of its teachings as a form of ethically engaged emancipation.[5]

I. “Think we must”: a brief critique of worlding in Westernized Modernity[6]

Many societies inspired by sociopolitical values associated with Westernized Modernity (WM) have come a long way in protecting individuals against some egregious forms of violence and excesses of power.[7] Classical liberal safeguards of human dignity, freedoms, and related frameworks for determining legal responsibility are valuable conquests that serve very important functions in diverse socio-political processes and institutions.[8] Nevertheless, underlying classical liberal notions of self and freedom are increasingly being subjected to criticism, ranging from ecology to neurosciences.[9] Unsurprisingly, many scholars have remarked that these notions reveal themselves to be useful conventions in some spheres, but not without their dangers.[10]

The ontological dimension of language production comprises its role in the continuous negotiation of what could or should be considered in the human survey of existents and what is possible in the world. I will refer to the process of ‘worlding’ as “the establishment of a particular perspective towards the raw avalanche of perceptions investing a subject’s awareness at each instant.”[11] In this context, a fundamental metaphysical problem arises when language is taken to be absolute, “unbound (ab-solutus) from any external constraint or from any other principle outside itself.”[12] WM is rooted in a problematic cosmogonic principle of absolute language: “truth is representation, and representation is truth.”[13] The world of measurable factuality that emerges “suddenly becomes the only possible ontological field.”[14] Beyond the (sometimes functional) manifestations of some conventions in legal and other spheres, many of us fail to see how other dimensions of our existence have been constrained to fit within the narrow world of WM.[15]

Notions of self have also fallen victim to absolute language. In the cosmology of WM, the self is often thought to be a mechanistic human body independent of everything else. The brain is believed to be the source of the epiphenomenon of an ego-consciousness possessing free will.[16] However, the mysterious Ego-Absconditus (‘hidden I’) at the cosmological limit of WM is only given citizenship as a form of ‘Abstract General Entity’ (AGE), when filtered through serial roles.[17] In particular, the roles of citizen, worker, and consumer occupy positions of cultural prominence. In general, these senses of self accentuate separation and strengthen egotistical reactivity.[18] Such metaphysics of the self end up shaping fundamental socio-political notions in WM’s worlding. To further connect the discourse of metaphysics with that of ethics, I now turn to a critique of the current state of the values hoisted by the French Revolution: freedom, equality and fraternity. Beyond France, similar values were meant to inspire (and are still said to inform) many of the liberal democracies of WM.

Along with freedom (examined next), the French Revolution called humanity to embrace the values of equality and fraternity. Although important differences do exist, countries all over the world struggle to address deficiencies of formalist equality (i.e. “all humans are equal before the law”) that fail to reach key issues of material inequality.[19] This seems to be an indicator that a felt experience of even human fraternity fails to take root in our cultural imaginaries[20]. In addition, non-exploitative forms of relating to the more-than-human world are often smothered in hegemonic WM cosmology.[21] The climate emergency is an undeniable rally call to question and surpass harmful anthropocentric beliefs and behaviors based on a sense of separation between humanity and nature.[22] In a multi-species ethics of sympoiesis or ‘wolding-with’ (in contrast to autopoiesis), beings learn to live and die in ‘response-ability’ with ‘companion species.’[23]

Taking the next value of freedom into consideration, we find that one aspect often fills the whole cultural stage: ‘external freedom’ of the separate ego-self qua AGE. What I mean by this is the liberty of an individual to materialize its desires.[24] Excessive focus on such ‘external freedom’ does not seem unrelated to many aggressive defenses of egotistical interests that are harmful to self, other sentient beings, and the biosphere. In the political sphere, the role of the citizen often manifests in the form of self-enclosure, segregation, and extreme polarization.[25] In parallel, a pervasive capitalist culture seeks to encode all possible human value in the roles of the worker and the consumer: living-to-work and working-to-consume.[26] This is leading to an all-devouring market sphere that threatens to monetize every aspect of our lives.[27] It is not hard to see how behavior aligned with self-cherishing or tribalism may easily follow, obstructing possibilities for understanding and mutual care.

Dimensions of existence that lack malleability to WM’s world-making machines of factuality, seriality, and measurement have been relegated to basements of cultural neglect.[28] This leaves us increasingly vulnerable to the exploitation of constant demands to surrender our attention, time, energy, and possessions at the altar of mindless consumerism, WM’s form of freedom par excellence. ‘Business as usual’ continues to accelerate the apocalyptic process of the ‘Sixth Great Extinction.’ In this context, Haraway reinterprets Hannah Arendt’s ‘banality of evil,’ equating it to an incapacity for deep ‘thinking-with’ companion species.[29]

The threat faced by humans and the whole biosphere exposes the irony of our self-destructive obsession with such problematic notions of self and freedom. To weave new strands of metaphysical and ethical discourse, let us opportunistically take advantage of this irony’s effect of “suspending reality.”[30] If we cannot even imagine a different world and ways of being alternative to our hegemonic cultural inheritances, we will remain trapped in the ruins of WM.[31]

Religious cultures: metaphysics attuned to paradox, ethics and internal freedom

This reality-system has obscured the cultural visibility of a second dimension of freedom, that I name ‘internal freedom.’ Though hardly conspicuous due to hegemonic cultural blinders, it is often explored in discussions on free will and ethics, historically found in fields like religion, philosophy, psychology and anthropology.[32] At a time when we desperately need inner resources for envisioning and embodying alternative worlds where ‘all beings may flourish,’ the deep wisdom these disciplines hold is failing to reach us on a wide cultural scale.[33] Many constructive discussions at the intersection of metaphysics, ethics, and contemplative practice await broader cultural consideration, and to be explained in skillful ways that consider the critical role of context. Motivations of internal freedom could hold great potential for prosocial and eco-conscious behavior, particularly when paired with sustained reflection on causes and conditions that promote suffering and well-being.

Over the past century, many westernized countries have witnessed growing interest in the wisdom ideals of South Asian spiritual traditions, their contemplative practices, and their ethical doctrines. More recently, the lively dialogue between Asian religious cultures and contemplative psychology is helping to make a foreign vision of ethics and contemplative practices more widely accessible and sometimes more understandable in Westernized societies. However, ethnocentric scientisms all too often draw problematic lines between ‘real, valuable, scientific practices’ and their ‘premodern, unscientific baggage,’ relegated to the status of a museum piece, a cultural curiosity.[34] Such quasi-colonial attitudes often desiccate alternative cosmologies that could inspire syncretic cultural fields for the embodiment of an ethics of sympoiesis.

How can we break free from the overwhelming force of convention and the Procrustean rigidities that plague WM’s cosmogony of absolute language?[35] Federico Campagna’s call for a ‘reconstruction of reality’ that leaves space for the non-conceptual and the ineffable can also be read as call to re-valorize neglected cultural strands that focus on immaterial aspects of mental life, while remembering that interdisciplinary dialogue can only bear fruit if we hold conventions lightly.[36] In parallel, a good starting point might be recovering a sense of intimacy in experience.[37] Given sustained reflection and embodied practices for investigation, religious cultures could help us transcend unskillful absolute views.

The reflections of Modernist Catholic theologian Friedrich von Hügel offer an insightful segue to some Buddhist ideas that I wish to employ in my reading of Bhuśuṇḍa’s tale. Von Hügel identifies three interrelated elements in religion: (i) the historical or institutional, (ii) the intellectual or speculative, and (iii) the mystical or experiential.[38] Warning against attempts to make any of these elements ‘the whole of religion,’ the theologian carves out a place for each of them in Catholic culture. This is by no means a rational synthesis, or a solution of ‘complexity’ within WM’s cosmology.[39] Rather, two levels of convention share a paradoxical relation between them, and with the third element that points to the ineffable or the non-conceptual.[40]

II. Elements for a Buddhist reading of the story of Bhuśuṇḍa

Surviving cultural manifestations of the roughly 2,500 year old Buddhist tradition also reveal metaphysics that leave space for the non-conceptual. I believe that this religious culture could inspire skillful notions of self and freedom for an ethics of compassion. In this section I present a Mahāyāna interpretation of some Buddhist concepts that inform my reading of Bhuśuṇḍa’s tale.[41]

Non-self and Interdependent arising

The doctrine of non-self (Skt. anātman) is at the earliest strata of Buddhist texts.[42] It should not be equated with a form of nihilism: what is being denied is a permanent self existing independently of everything else (endowed with intrinsic existence —Skt. svabhāva—).[43] Such a reificatory view is considered a root cause of avoidable suffering; hence, the Buddhist path aims to dissolve bounded and unchanging notions of self. The cartography of such problematic ways of thinking and acting is represented in the 12 links of interdependent arising (Skt. pratītya-samutpāda).[44] A view of self through the lens of interdependent arising is said to be a more skillful path, since it helps to avoid suffering that arises from ignorance (Skt. avidyā) of impermanence and the constellation of causes and conditions inherent in oneself and others.[45] The twin forces of attraction and aversion (Skt. rāga-dveṣa) are seen as sprouting from ignorance.

The conventional self is seen as the combination of five categories or “heaps” (Skt. skandhas): (i) the material (Skt. rūpa), (ii) sensation or feeling-tone (Skt. vedanā): pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral, (iii) perception or symbolic interpretation (Skt. samjñā), (iv) mental formations, or mental conditioning (Skt. samskāra), and (v) consciousness (Skt. viijñāna).[46] Consciousness is not dissociated from the other four categories: “it resides in life itself, it is experience itself seen from a certain angle, reoriented.”[47] All in all, the conventional self can be interpreted as a concatenation of these cyclically repeated causes in interdependence with the ‘external.’

The Two Truths and Emptiness

Not unlike von Hügel’s threefold model of religion, the Buddhist doctrine of the two truths (Skt. dvasatya) prevents the collapsing of the background of essence onto the stage of existence, absolute language’s obscuration of all other possible realities.[48]

The Mahāyāna interpretation of the two truths was built on an earlier idea of the Pāli canon: the Buddha’s teachings have the pragmatic aim of leading to the cessation of suffering, once attained there should be no blind clinging to them.[49] In some Mahāyāna Perfection of Wisdom (Skt. prajñā-pāramitā) sūtras, the ultimate validity of traditional Buddhist teachings is denied.[50] The Buddha himself explains that they are not are not to be considered definitive, since the ultimate reality is ineffable and only accessible by transcending words and concepts altogether.[51] However, the literal level of the canonical teachings was not completely denied; these still have pedagogical value as provisional teachings that reflect relative truth.[52] The Madhyamaka school presented itself as a philosophical middle way between the extremes of eternalism and nihilism.[53] Nāgārjuna, its foundational figure, based his doctrine of emptiness (Skt. śūnyatā) on the dyad of conventional (Skt. saṃvṛti) and ultimate (Skt. paramārtha) truths (Skt. satya) found in the Perfection of Wisdom sūtras.[54]

Closely linked, the doctrine of emptiness can be read as an extension of the approach of the non-self doctrine to all phenomena (Skt. dhārma-s).[55] Madhyamaka dialectics seek to critically examine and reject all logical alternatives that posit self-existing phenomena.[56] In the later Buddhist tradition, this kind of “apophatic” analysis has been used to induce in the aspirant a rational certainty of emptiness, compounded with meditative practice.[57] On a conventional level, emptiness is expressed as the interdependent arising of phenomena and labelled conceptually as such.[58] In summary, all conventional phenomena are seen as interdependent and impermanent.

The Buddha, the Bodhisattva, and The Three Disciplines

The Buddha and the Bodhisattva are archetypes that embody the goal and training in altruistic freedom. The Buddhist approach to spirituality can be interpreted as a systematic dismantling of unskillful (Skt. akuśala) notions of self and freedom, and the concurrent cultivation of skillful (Skt. kuśala) opposites.[59] In this path, wisdom and compassion form an indivisible pair.

Out of great compassion (Skt. mahā-karuṇā), a Bodhisattva vows to attain the supreme goal of buddhahood, maximizing their capacity to help all sentient beings attain freedom from suffering.[60] The Mahāyāna innovation of the bodhisattva vow (Skt. bodhisattva-saṃvara) encapsulates this great commitment, made accessible to lay practitioners, unlike the earlier monastic vows (Skt. prātimokṣa-saṃvara).[61] In this titanic task, the aspirant is driven by an unwavering altruistic mindset (Skt. bodhicitta, lit. “mind of awakening”).[62] The Bodhisattva’s profound affective identification with suffering sentient beings is a natural consequence of an experiential, embodied understanding of non-self, emptiness and interdependent origination.[63] Grounded in wisdom, this practical reorientation to solidarity with the eradication of suffering allows an ascension over the paralyzing marshes of cynicism and existential pessimism.[64]

The framework of the three disciplines (Skt. triśikṣā) of (i) meditation/concentration (Skt. samādhi), (ii) wisdom/insight (Skt. prajñā), and (iii) ethics/virtue (Skt. śīla) will clarify the levels of interconnected discourses and practices of metaphysics, ethics, and contemplation in the narrative of Bhuśuṇḍa.[65] Meditation (i.e. the myriad methods and practices in general) helps to expose unskillful notions of self and freedom, as well as to cultivate embodied, wise compassion.[66] Wisdom is the result of insight into the nature of suffering and its causes, and an intuition of emptiness qua dependent arising, leading to the abandonment of reificatory habits.[67] The ethics of compassion manifests outwardly as conduct that aims to avoid harm, seeking instead to alleviate suffering for oneself and others.[68] Rooted internally as the cultivation of the altruistic mindset, considerations of mental causality are highlighted. Intimately observing our mental life is a first step for learning to skillfully work with it (i.e. ‘mental cultivation’), thus developing an ethics of compassion that informs notions of freedom.[69]

Caveat lector! The relationship between ethics and emptiness is far from simple: can an ethical doctrine expressed merely in the register of convention be “be taken seriously as a genuine theory of value” or does it degenerate “into either moral anti-realism or relativism”?[70] I believe that a charge of nihilism can easily be rebutted through an adequate understanding of Madhyamaka philosophy, but the issue of ethical relativism is more complex.[71] Suffice it to say for the purposes of this article that good arguments have been put forth in support of critical-constructive interpretations, without degenerating into romantic orientalism.[72]

Yogācāra idealism

Yogācāra thought, also known as “mind-only” (Skt. cittamātra), emerged as a later interpretation of the concept of emptiness.[73] These texts tend to emphasize the role of mind (Skt. citta) or consciousness (Skt. vijñāna) in human experience, and explain how ignorance about ultimate reality causes us to mistakenly perceive phenomena.[74] The functioning of consciousness gravitates around two notions: afflicted mentation (Skt. kliṣṭa-manas), and basic consciousness (Skt. ālaya-vijñāna), a field that persists even in the absence of all mental processes. The process of perception of phenomena is explained as the sprouting of karmic seeds (Skt. bīja) and predispositions or conditioning (Skt. vāsanā, lit. ‘perfumations’) on the basic consciousness.[75] In Higgins’ words: “that mind (citta), under the influence of defiled ego-mind (kliṣṭamanas), has both intentional (object-intending) and reflexive (‘I-intending’) [Skt. svasaṃvedana] operations that structure experience in terms of an ‘I’ (subject) and ‘mine’ (object).”[76]

III. The story of Bhuśuṇḍa in the Yoga Vāsiṣṭha

As discussed in the introduction, the YV is a syncretic text that draws from Trika Śaivism, Yogācāra Buddhism, and Upaniṣadic Advaita thought.[77] The previous sections laid a foundation in terms of relevance and vocabulary for a Buddhist reading of the story of Bhuśuṇḍa.

Metaphysics and ethics in the tale of Bhuśuṇḍa

At the basic narrative layer, Vasiṣṭha sets the stage in metaphysical terms: “In the infinite and indivisible consciousness, there is a mirage-like world-appearance in one corner, as it were”.[78] This reference lends itself to a non-dual Yogācāra reading, grounded on the doctrine of the two truths. Vasiṣṭha then tells his royal pupil Rāma that he felt inspired to meet the crow Bhuśuṇḍa upon hearing that he was the longest-living enlightened being on heaven and earth. Vasiṣṭha journeyed to the lofty summit of mount Meru, where he discovered the radiant, “wish-fulfilling tree” Cūta.[79] Macro-microcosmic correspondences abound in the description of the tale’s setting, couched in metaphors and similes.[80]

Vasiṣṭha narrates that many celestial beings and perfected sages dwelt on the enormous tree. There lived Bhuśuṇḍa, among birds that served as vehicles for the gods.[81] Vasiṣṭha was awestruck at the sight of the majestic and serene crow, who had “lived through several world-cycles (…) free from I-ness and mine-ness (…) the friend and relation of all.”[82] He then praised the crow’s supreme peacefulness, attainment of the highest wisdom of self-knowledge, and his freedom from “the net of illusion known as world-appearance.”[83] I will explain how these qualities might inspire notions of self and freedom for a multi-species ethics of sympoiesis (worlding-with).

The biography of Bhuśuṇḍa

Let us eavesdrop on the second narrative layer, where Vasiṣṭha asks several questions regarding the crow’s longevity. Bhuśuṇḍa replies that he would answer by narrating his biography, so inspiring that it could destroy the sins of those who listened.

This fantastic story is a third narrative layer that begins with Bhuśuṇḍa’s conception. A group of fearsome female deities assembled to worship the divinities Tumburu and Bhairava (a form of Śiva), by engaging in left-handed ritual.[84] When the deities and the animal vehicles became intoxicated, the powerful crow Caṇḍa, vehicle of the deity Alambuṣā, mated with a group of swans belonging to the goddess Brāhmī. These became pregnant and birthed 21 sons, including Bhuśuṇḍa. They all worshipped Brāhmī, who bestowed on them the boons of self-knowledge and liberation from the “the dragnet known as the world-appearance, after having cut the shackles of vāsanā or mental conditioning.”[85] Their father then directed them to take nest in the wish-fulfilling tree.

An enlightened teacher in the form of a crow and the circumstances of his conception is perhaps the most salient group of metaphors.[86] The often disdained species points to a non-dual philosophy, and Timalsina sees in this an indicator that the yoga of Bhuśūṇḍa originates in the lower strata of society.[87] It could also be read as a metaphor for bodies in general: “Bhuśūṇḍa nevertheless indicates that while there may not be a reason for clinging to the body, there is equally no point in rejecting it.”[88] This brings to mind the Buddhist doctrine of emptiness, and its tantric corollary that the potential for enlightenment is present in everything.[89] The importance of ‘internal freedom’ is evinced in the allusion to liberation from mental conditioning (Skt. vāsanā) and reification (Skt. samāropa) of the “world-appearance.”[90]

Returning to the narration, we hear that Bhuśūṇḍa’s brothers have already perished. When Vasiṣṭha enquires about the contrast of his extreme longevity, the crow replies that he has “remained immersed in the self, happy and contented (…) having abandoned vain activities that are but torment of the body and the mind.”[91] This reference may be interpreted as the need for discernment of the causes and conditions that lead to suffering (i.e. ‘mental cultivation’). Two contemplative techniques that aid this process are then introduced: prāṇāyāma and a series of elemental dhāraṇās.

Against a cosmological backdrop of recurring world-cycles of creation and destruction, Bhuśuṇḍa fearlessly proclaims: “This wish-fulfilling tree is not shaken by the various natural calamities nor by the cataclysms caused by living beings.”[92] Successive concentrations (Skt. dhāraṇās) on the phenomenological qualities of various elements allow the crow to experientially identify with cosmic space, resting in a state of freedom from mental modifications during recurring apocalypses.[93] I would like to suggest an added layer of meaning in terms of worlding: cosmological stories are fragile things, and Bhuśuṇḍa has learned to survive their apocalypses through contemplative practice.[94]

The fabulous crow narrates how he has witnessed the universe being created ten times, only to be destroyed later. In this cosmic drama of mythical proportions, the gods and humans play alternative roles, the directions change, and Bhuśuṇḍa reveals that he has even met Vasiṣṭha in seven previous incarnations. Akin to a Yogācāra view, Bhuśuṇḍa explains that all is illusory appearance, neither real nor unreal, since the only underlying reality to this drama is “the movement of energy within the cosmic consciousness.”[95] This ‘flimsy fixity’ decenters our notions of reality and challenges our reificatory habits.[96]

The doctrine of the two truths is hinted at in Bhuśūṇḍa’s description of the outcome of the practices, which may be read as an equanimous, embodied intuition of emptiness: “We neither accept nor reject; we appear to be but we are not what appears to be.”[97] This might initially seem like an aloof position of ‘contemplative navel-gazing,’ but Bhuśuṇḍa soon acknowledges the rightful place of aesthetics and the conventions of subject and object for engaging with the world: “Though we engage ourselves in diverse activities, we do not get drowned in mental modifications and we never lose contact with the reality.”[98]

Urged by Vasiṣṭha’s insistent inquiry on the causes of his extreme longevity, the mythical being later states that it is due to “the will of the supreme being” and that “one cannot fathom nor measure what has to be.”[99] Beyond (i) the pragmatic conventions for referring to distinct beings, and (ii) the convention of a non-dual idealism, the spiritual teacher acknowledges (iii) an overflowing, ineffable dimension. Against extreme views that absolutize the conventional or the non-conceptual, Bhuśuṇḍa thus advocates a “stereoscopic view” that allows for skillful swaying across metaphysical dimensions, without losing a footing in the continuous, raw avalanche of perceptions.[100]

The tide of the crow’s metaphysical discourse now flows to more concrete ethical advice in terms of internal freedom: he says that death does not touch those who are free from “attraction and aversion” (Skt. rāga-dveṣa). Cognitive and emotional afflictions (Skt. kleśa) that are to be avoided, such as anxiety, greed, anger, lust, etc., arise out of ignorance (Skt. avidyā).[101] Again, Bhuśuṇḍa explains that this state of supreme wisdom does not equate to inactivity or ethical indifference, as “he is always engaged in appropriate action.”[102] Such wise and ethical action spontaneously manifests when the illusion of separation has been exposed: “One should slay the ghost of duality or division and fix the heart on the one truth,” leading to joy and auspicious qualities.[103] Awareness of the impermanence of the “world-appearance,” and the vision of the one infinite consciousness are the twin roots of that blessed state. Although the Advaita influence is undeniable, these statements might also lend themselves to a Yogācāra reading.

Bhuśuṇḍa’s yoga of prāṇa

In the following chapters, Bhuśuṇḍa alludes to two contemplative methods to reach the supreme state: (i) the contemplation of the self, devoid of mentation; and (ii) the contemplation of prāṇa. Bhuśuṇḍa explains that he decided to adopt the second method, since the first path proves difficult for him. The subsequent explanation abounds with subtle body references.[104]

In a general sense, prāṇa refers to the life-force that animates the body and allows the organs to carry out their functions.[105] This ‘life-force’ is divided into several ‘vital airs’ with specific roles. What follows is a poetic reference to the most important pair, prāṇa (in a second usage, stricto sensu), and apāna: “I am devoted to them, which are free from fatigue, which shine like the sun and the moon in the heart, which are like the cartwheels of the mind which is the guardian of the city known as the body, which are the favourite horses of the king known as ego-sense.”[106]

What does it mean to devote oneself to these two vital airs? Bhuśuṇḍa explains that the ultimate may be directly perceived by deeply concentrating on the kumbhakas, the gaps between exhalation (Skt. recaka) and inhalation (Skt. puraka): “That which IS after the prāṇa and the apāna have ceased to be and which is in the middle between prāṇa and apāna— I contemplate that infinite consciousness (…) which enables the prāṇa to function and which is the cause of all causes. I take refuge in that supreme being.”[107] Intervals, be it between two thoughts, breaths or two states of consciousness, are seen in Śaivism as “cracks in the ordinariness of things” through which one may glimpse the omnipresent non-dual consciousness.[108] Not unlike von Hügel’s mystic element of religion, this contemplation of the non-conceptual calls us to hold convention lightly.[109]

This sway back to the ineffable might seem like an escape to the other-worldly, but the goal is a state of embodied liberation (Skt. jīvanmukti): “Whether one is going or standing, awake or asleep, these vital airs —which are naturally restless— are restrained by these practices. (…) who knows these kumbhakas is not the doer of these actions.”[110] An affirmation of corporeality and engagement with the world accompanies the dismantling of the sense of a separate ego-self. In my proposed reading, the sense of spaciousness experienced by observing the gaps of the breathing process acts as a safeguard against two reificatory tendencies highlighted in Yogācāra philosophy: reflexive and intentional. This process concurrently cultivates internal freedom, leading to a state of peace where an ethics compassion and multi-species sympoiesis can take root. Thus speaks Bhuśuṇḍa: “I do not contemplate either the past or the future: my attention is constantly directed to the present. I do what has to be done in the present, without thinking of the results.”[111]

Ethical teachings are never far from these lofty discussions on metaphysics and instructions for embodied contemplative practice. The brahma-vihāras (lit. abodes of Brahma) or apramāṇas (lit. immeasurables) are simultaneously four qualities of the enlightened mind and practices for its cultivation: (i) lovingkindness or benevolence (Skt. maitrī), (ii) compassion (Skt. karuṇā), (iii) sympathetic joy (Skt. muditā) and (iv) equanimity (Skt. upekṣā).[112] Bhuśuṇḍa’s solid grounding on a state of equanimity allows him to spontaneously perform ethical action without attachment to the results. The remaining three attitudes are also praised in the tale: “I rejoice with the happy ones and share the grief of the grief-stricken, for I am the friend of all, knowing that I belong to none and none belongs to me.”[113] Nourished by the tides of Bhuśuṇḍa’s metaphysical, ethical, and contemplative teachings, Vasiṣṭha gratefully bids farewell.

Conclusion: towards an ethics of sympoiesis

Advice on self and freedom for engaged emancipation

Returning to the basic narrative layer, Vasiṣṭha advises Rāma to live like Bhuśuṇḍa and practice his prāṇāyāma. To dismantle reificatory habits, Buddhist and advaita views of self are posited as equally valid remedies: “Either realize that ‘I am not and these experiences are not mine’ or know that ‘I am everything’: you will be free from the lure of world-appearance. Both of these attitudes are good: adopt the one that suits you. You will be freed from attraction and aversion (rāga-dveṣa).”[114]

Discouraging dependence on divine intervention, the sage praises “supreme self-effort” and wisdom to rise above the wheel of the birth and death (Skt. saṃsāra).[115] In a final piece of advice, Vasiṣṭha encourages the archetypal ruler to wisely and fearlessly engage himself in state affairs: “They who have laid this ghost [the ego-sense] are the good people who render some service to this world.”[116] We can conclude that throughout the three narrative layers, skillful notions of self and freedom fostered by contemplative practice are framed in an ethics of altruism.

Apocalypse and Westernized Modernity

Are our inherited, hegemonic cultural notions of self and freedom skillful ‘metaphors to live by’?[117] Can they truly offer the inner resources we urgently need to imagine and materialize effective solutions to contemporary ethical challenges? We continue to think of ourselves as ‘bounded individuals,’ and obsess over harmful forms of external freedoms. The constant barrage of conditioning and influencing techniques wielded by egotistical and short-sighted political and economic powers quietly erode our internal dimension of freedom.[118] While our mental weaknesses are exploited at a massive scale through the use of technology, the biosphere is threatened by anthropogenic climate change. As our internal freedoms languish and wither outside of our cultural blinders, we are left powerless to effectively respond to serious challenges.

Engaged emancipation: wisdom and compassion for sympoiesis

In a cosmos of emptiness and interdependent origination, the Mahāyāna aims at freedom from suffering by means of the altruistic cultivation of wisdom and compassion. From this Buddhist perspective, aligning notions of self and freedom with an ethics of compassion is an urgent concern. The discussion on motives, intention, and mental causality comes to the forefront, fostering eco-conscious and prosocial motivations instead of being surrendered to existing individual habits and cultural dynamics. Internal freedom is thus the liberation from the tyranny of compulsive attraction and aversion that lead to suffering. Unskillful notions of self (and other forms of reification) are at the root of such reactivity.

WM’s narrow worlding of absolute language, ‘bounded individuals,’ and mindless consumerism is leading us to an environmental catastrophe, that further exposes the self-destructiveness of our notions of reality. In this article, I suggested a Buddhist reading of the tale of Bhuśuṇḍa that weaves strands of metaphysics, ethics, and contemplative practice to offer inspiration for new forms of worlding.[121] This inspiration from religious culture has the added benefit of leaving space for the ineffable or the non-conceptual, avoiding the serious pitfalls of absolute language.

Set against a background of recurring apocalypses, Bhuśuṇḍa’s tale decenters our hegemonic notions of reality.[122] Through its metaphysics of ‘flimsy fixity,’ and its instructions on contemplative practices, it allows us to deeply interrogate our ideals of wisdom in embodied ways. By taking the immateriality of mental life seriously and dismantling unskillful notions of self and freedom, we can cultivate the inner dimension of freedom. I suggest that this is a fertile field for an compassionate ethics of sympoiesis (‘worlding with’) to arise. Practical ethical advice is also salient in the four attitudes of equanimity, lovingkindness, sympathetic joy, and compassion. Thus, through the transformation of our notions of self and freedom, the YV advocates for a form of engaged emancipation similar to that of the Buddhist bodhisattva.[123] In summary, Bhuśuṇḍa’s teachings offer inspiration for a sympoietic reconstruction of reality in a context of social turmoil and ecological crisis.[124]

NOTES

[1] For a Sanskrit recension in two tomes, see {[Vālmīki?], 1937, #119957}. There is a complete English translation in four tomes (Vihāri-lāla, Mitra 1891, 1893, 1898, 1899), but its quality has been questioned.

[2] {Timalsina, 2011, #57349}, 304.

[3] {Timalsina, 2011, #57349}, 303; {Chapple and Chakrabarti, 2015, #288311}, ix.

[4] I will quote from Swami Venkatesananda’s English rendering {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 346-66. For the unabridged translation, see {[Vālmīki?], 1898, #136922}, 75-145. For the Sanskrit version, see {[Vālmīki?], 1937, #50463}, 802-33/८०२-३३.

[5] I borrow this term from the title of a collection of essays on the YV, {Chapple and Chakrabarti, 2015, #288311}

[6] “Think we must. (…) Let us never cease from thinking—what is this ‘civilization’ in which we find ourselves? (…) Where in short is it leading us, the procession of the sons of educated men?” {Woolf, 1938, #24466}, 60. For a discussion of Woolf’s thought through a feminist ecological lens, see {Haraway, 2016, #298517}, 130.

[7] See Federico Campagna’s excellent analysis of ‘Westernized Modernity’ and comparison to archaic modes of worlding {Campagna, 2018, #73846}. A classic critique of the legal and punitive practices of the Ancien Régime is Dei deliti e delle pene. English translation {di Beccaria, 1995, #140415}

[8] Italian scholar Luigi Ferrajoli has published perhaps the most sophisticated theory of constitutional guarantees in the Romano-Germanic tradition. It has not been translated into English, perhaps due to structural differences with Common Law systems. Spanish translation {Ferrajoli, 1995, #136920}.

[9] From an ecological perspective: “What happens when human exceptionalism and bounded individualism, those old saws of Western philosophy and political economics, become unthinkable in the best sciences, whether natural or social? Seriously unthinkable: not available to think with” {Haraway, 2016, #298517}, 30. For a critical discussion of some neuroscientific negations of free will in Spanish, see {Arias Gutiérrez, 2014, #32894}, 56-83.

[10] The debate between iusnaturalism and legal positivism has long pointed at the conventional dimension of the law. See Kelsen’s Was ist Gerechtigkeit? English translation {Kelsen, 1973, #290445}, 1-26. For an insightful discussion in Spanish on the dangers of the disconnection between the pragmatic dimension of language and the text of the law, see {López Medina, 2008, #27098}. For discussions on more dramatic issues in the field of criminal law, see the work of the Norwegian critical criminologists Nils Christie and Thomas Mathiesen, widely translated.

[11] {Campagna, 2021, #258711}, 172. The following description is particularly suggestive: “The flow of perceptions that constitutes our experience of reality is more akin to the onslaught of an oceanic tide – immense, faceless and undivided. At each instant, our awareness attempts to canalize perceptions within the frame of sense of a ‘world’ (kosmos, mundus): a newly created landscape where our experience can unfold, and our intentions can be projected.” {Campagna, 2021, #258711}, 14. For a discussion of the notion of worlding in connection to Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘machine,’ and Heidegger’s ‘Dasein,’ see {Campagna, 2021, #258711}, 13n20, 14n23. For a critique of Kantian and Heideggerian modes of worlding as globalizing and anthropocentric, see {Haraway, 2016, #298517}, 11.

[12] {Campagna, 2018, #73846}, 66.

[13] {Campagna, 2018, #73846}, 62.

[14] {Campagna, 2018, #73846}, 65-6.

[15] For a discussion of the risks posed to notions of reality (understood as “the segment stretching between the fuzzy boundaries of existence and essence”), see {Campagna, 2018, #73846}, 109-11.

[16] For an excellent discussion in terms of philosophy of science, in Spanish, see the work of astrophysicist and Sanskrit scholar Juan Arnau, {Arnau Navarro, 2017, #158341}. Arnau was a student of the late Luis O. Gómez, Buddhist studies professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

[17] {Campagna, 2018, #73846}, 51-2, 84-9, 95-101.

[18] Rhonda Magee´s work explains some of these issues {Magee, 2019, #67391}.

[19] This brings to mind the poignant words of Anatole France: “the majestic equality of the law, which forbids both the rich and the poor from sleeping under the bridges, begging on the streets, and stealing bread” (my translation from the original: “la majestueuse égalité des lois, qui interdit au riche comme au pauvre de coucher sous les ponts, de mendier dans les rues et de voler du pain.” {France, 1894, #291777}, 118.

[20] For a classic analysis of individualism in American society, see {Bellah et al., 1996, #226652}. See also Franco Berardi’s call towards a subjectivity of solidarity in the context of a ‘landscape of anxiety’ characterized by a growing “internalisation of the refusal to feel the emotions of others, and possibly also one’s own emotions” {Berardi, 2021, #112705}. On the necessity of challenging human exceptionalism, see {Haraway, 2016, #298517}, 49-51.

[21] See Heidegger’s discussion of nature as Bestand (standing-reserve) in Die Frage nach der Technik. English translation {Heidegger, 1977, #236978}, 17-49. For an analysis of this problematic way of ‘enframing’ (das Gestell) in WM, see {Campagna, 2018, #73846}, 24-6, 39-41.

[22] On the dangers of separation from and opposition to nature, see {Morton, 2007, #230862}, 125-35.

[23] For a thought-provoking exploration, see {Haraway, 2016, #298517}, 33-57, 58-98.

[24] In this context, I exclude Epictetus’ ‘freedom of the slave’ (through the extinguishing of desires). My usage comprises two forms of freedom often employed in political discourse: positive and negative. See {Berlin and Harris, 2002, #214604}, 30-54.

[25] See, in particular, chapter 7 of {Magee, 2019, #67391}

[26] For an insightful —though not unproblematic— anarchist critique, see {Campagna, 2013, #148222}

[27] {Campagna, 2018, #73846}, 87-9.

[28] See for all, Arnau’s tour de force of the history of imagination, in Spanish {Arnau, 2020, #198778}

[29] “This quality was not an emotional lack, a lack of compassion, although surely that was true of Eichmann, but a deeper surrender to what I would call immateriality, inconsequentiality, or, in Arendt’s and also my idiom, thoughtlessness. Eichmann was astralized right out of the muddle of thinking into the practice of business as usual no matter what. There was no way the world could become for Eichmann and his heirs—us?—a ‘matter of care.’”{Haraway, 2016, #298517}, 36. For Arendt’s analysis, see {Arendt, 2006, #36291}, 287-90.

[30] See the quote from Franco Berardi’s unpublished manuscript Come Finirà in {Campagna, 2021, #258711}, 125.

[31] A recent study on climate anxiety and moral injury across young generation speaks volumes {Hickman et al., 2021, #88415}

[32] What I mean by ‘internal freedom’ bears certain similarity to Isaiah Berlin’s ‘spiritual freedom’ {Berlin and Harris, 2002, #214604}, 31-2. However, it is most directly inspired by Juan Arnau’s fine body of work (in Spanish) across Western philosophy and Sanskrit texts. In particular, I draw inspiration from his critique of freedom (via William James, Henri Bergson, and Alfred North Whitehead), in {Arnau, 2016, #44405}, and his notion of cultura mental (‘mental cultivation’) rooted in Sanskrit philosophy, especially Vasubandhu’s works, {Arnau Navarro, 2012, #129710}, 106-9 (see also infra). Unfortunately, his works have not been translated into English.

[33] I borrow the expression from the title of a collaborative tome {Hartman, 2018, #293561}. I am, however, aware of the complex issues of ‘inter-species collaboration,’ as pointed out in Haraway’s more modest call for “partial recuperation and getting on together” see {Haraway, 2016, #298517}, 10-29.

[34] This brings to mind Meyer’s notion of ‘the damned topics of Buddhist philosophy’ {Meyers, 2016, #155152}. For a critical discussion on Buddhism and cognitive science, see {Garfield, 2011, #62826}. More broadly, on materially-reductive scientisms {Arnau Navarro, 2017, #158341}, 273-89.

[35] In the Greek myth, the blacksmith Procrustes would offer travelers shelter and then hold them captive, painfully stretching or cutting their bodies until they fit the exact measurements of the bed {Hamilton, 1998, #245254}, 210-1. The arbitrary standard and the utter disregard for the harm caused may illustrate a serious pitfall in the intercultural dialogue. We should truly interrogate our cultural assumptions from a place of epistemological humility if we wish to leave space for a new understanding to arise.

[36] {Campagna, 2018, #73846}. The case for interdisciplinary dialogue was masterfully made by Spanish perspectivalist philosopher Ortega y Gasset, who criticized ‘la barbarie de los especialistas’ (‘the barbarism of specialization’). English translation {Ortega y Gasset, 1957, #145069}, 107-14.

[37] For a discussion of the “inner world as a precondition for experience,” in South Asian traditions, see {Chapple, 2020, #134240}, 1-21. For a discussion in terms of Christian contemplative ecology, see {Christie, 2012, #118401}, 225-69.

[38] {von Hügel, 1909, #125807}, 58-82.

[39] On WM’s tendency to reduce metaphysical disorder to mere ‘complexity’ (not in connection to von Hügel’s framework), see {Campagna, 2021, #258711}, 78-85.

[40] On the obvious importance of the conventional: “Without such divisions, arbitrary as they may be, I would be unable to address anything, to take anything or to repel anything – reality would no longer be a world, but an uninhabitable, undivided ocean of perceptions. Ultimately, a subject cannot count on there being such thing as a world, existing undisturbed by itself: they must rely on the magic of a metaphysical storytelling, standing as a world for those who perform it.” {Campagna, 2021, #258711}, 15.

[41] Beyond the ideal of the Arhat, who strives towards individual liberation, the Mahāyāna tradition puts the accent on altruism. Although the altruistic Bodhisattva ideal was not unknown to earlier Buddhist traditions, it was perceived as an extremely difficult goal, pursued only by extraordinary individuals {Powers, 2007, #22546}, 111.

[42] The Pali Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta (SN 22:59) is considered one of the Buddha’s first discourses. English translation {Thera, 2010, #8745}

[43] {Gethin, 1998, #229497}, 159-62.

[44] This model is seen as presenting some regularities of the human psyche, considered vital information for some practices of mindfulness. These are explained in the Mahā Nidāna Sutta (DN 15). English translation {Bhikkhu, ND, #258776}

[45] {Gethin, 1998, #229497}, 149-59.

[46] The Milindapañha is a popular exposition of the five aggregates, framed as a discussion between the Indo-Greek king Menander and the Buddhist monk Nāgasena. English translation {Kelley, 2013, #295067}. For a discussion of the five aggregates and alternative translations, see {Snellgrove, 2004, #55806}, 19-23.

[47] My translation from the original: “reside en la vida misma, es la propia experiencia vista desde cierto ángulo, reorientada” {Arnau Navarro, 2017, #252244}, 148.

[48] I borrow the simile from the work of Campagna, where it is not used in the context of Buddhist philosophy, {Campagna, 2018, #73846}, 109-11.

[49] {Federman, 2009, #250540}, 126-7.

[50] These Mahāyāna scriptures often presented their distinctive religious doctrines as being special teachings of the Buddha communicated secretly to select disciples {McMahan, 2002, #240487}, 102-4. The perfection of wisdom can be seen as the ideal of the direct realization of the ultimate truth {Powers, 2007, #22546}, 120. It is considered supreme because its cultivation brings about a state of spontaneous development of all other perfections, maximizing the potential to help all sentient beings realize enlightenment {Snellgrove, 2004, #55806}, 91–3. For an English translation of one of the most well-known sūtras in this category, the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, see {Conze, 1973, #82025}

[51] {van Schaik, 2015, #203377}, 29.

[52] {Federman, 2009, #250540}, 125. The earlier teachings of the canonical sūtras were understood as manifestation of the skillful means (Skt. upāya-kauṣalya) of the Buddha, who dexterously adapted his teachings to make them useful to a wider audience {Blumenthal, 2013, #236942}, 87. Skillful means also describes the teachings and actions undertaken by those who follow the Mahāyāna path to help all sentient beings realize enlightenment {Powers, 2007, #22546}, 126.

[53] {Blumenthal, 2013, #236942}, 90. Madhyamaka thought originated around 2nd centuries CE in the works of Nāgārjuna, an Indian sage who systematized his interpretations of the Perfection of Wisdom sūtras and engaged in numerous debates. His “Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way” (Skt. mūla-madhyamaka-kārikā) is the most influential Madhyamaka work {Blumenthal, 2013, #236942}, 89-90. English translation {Nāgārjuna et al., 2013, #32300}

[54] {Ruegg, 2010, #169436}, 40.

[55] In opposition to the approach of some Abhidharma distinctions between pure and impure dhārmas, Nāgārjuna argued that all are ultimately empty, lacking substantiality or intrinsic reality as independent or autonomous things-in-themselves {Westerhoff, 2018, #204094}, 47-8.

[56] {Westerhoff, 2018, #204094}, 142-6.

[57] {Pettit and Mipham, 1999, #193747}, 3. For a practical introduction to the Madhyamaka combination of analysis and contemplation from a Tibetan perspective, see {Bstan-ʼdzin-rgya-mtsho, 2006, #229056}

[58] {Ruegg, 2010, #169436}, 39-54.

[59] In line with the pragmatic orientation of Buddhism explained above, the distinction is based on an embodied discernment of how and when some views and behaviors may lead to suffering. For a discussion based on the Pāli sūttas, see {Cozort and Shields, 2018, #274595}, 11-3.

[60] {Blumenthal, 2013, #236942}, 86-7.

[61] {Williams, 2009, #11254}, 35-8. Three important sources for the Bodhisattva vows and precepts are the eighteenth chapter of the Avataṃsaka Sūtra, the Brahmajāla Sūtra, and the third chapter of Śāntideva’s Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra. English translations, respectively, {Cleary, 1993, #104370}, 425-37; {Muller and Tanaka, 2017, #139511}; {Śāntideva, 1997, #251861}, 115-35.

[62] {Gethin, 1998, #229497}, 229. For a classic source on bodhicitta, see the first chapter of Śāntideva’s Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra. English translation {Śāntideva, 1997, #251861}, 17-22. For an extensive study on bodhicitta across Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, see {Wangchuk, 2007, #165882}

[63] For a discussion on the spontaneity of a Buddha’s activity from a Yogācāra perspective, see {Williams, 2009, #11254}, 102.

[64] Budismo esencial, 147?

[65] For a reference to the three disciplines in terms of the Noble Eightfold Path, see the Pali Cūḷa Vedalla Sutta (MN 44). English translation {Bhikkhu, ND, #271257}. For a reference in the Mahāyāna, see Nāgārjuna’s Suhrllekha{Nāgārjuna and Dharmamitra, 2009, #288772}, 39.

[66] For the classic source on the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, see the Pāli Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta (MN 10). English translation {Bhikkhu, ND, #171007}. For a contemporary discussion from the perspective of contemplative psychology, see {Loizzo, 2012, #3827}, 55-8.

[67] See supra. Another important source is the ninth chapter of Śāntideva’s Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra. English translation {Śāntideva, 1997, #251861}, 115-35.

[68] Three key sources are the Pāli Sāla Sāleyyaka Sutta (MN 41), Dhammika Sutta (SN 2.14), and Mettā Sutta (AN 4:125). English translations, respectively {Bhikkhu, ND, #167078}, {Ireland, 2013, #22563}, {Bhikkhu, ND, #285457}. In the Mahāyāna, See supra

[69] On the expression ‘mental cultivation’ (cultura mental) see supra. Some additional selections from Juan Arnau’s publications: on ’mental cultivation’ in connection to Vasubandhu’s and Berkeley’s thought {Arnau Navarro and Mellizo, 2011, #112357}; more broadly, {Arnau, 2020, #198778}, and {Arnau Navarro, 2017, #158341}. A discussion on freedom and ethics in South Asian, traditions accompanied by sharp critique of Western ethnocentric scholarship can be found in {Ranganathan, 2017, #142387}, xii-122.

[70] {Cowherds, 2015, #171931}, 3.

[71] For an excellent exploration of the conventional dimension of reality in Madhyamaka philosophy, see {Cowherds, 2011, #283834}

[72] Space constraints prevent me from explaining this further. For an insightful critical-constructive position, see {Westerhoff, 2015, #66302}, and {Priest, 2015, #71299}. Contra, see Kripal’s essay on the ethical status of mysticism in Indian traditions, which includes a critique of romantic orientalism {Barnard and Kripal, 2002, #5140}, 15-69. For a critical analysis of Buddhist mysticism and ethics, and an interesting discussion on the ethics of “more physical, instinctive sensuality,” see {Barnard and Kripal, 2002, #5140}, 265-87.

[73] {Blumenthal, 2013, #236942}, 92-4. Two important scriptures of this tradition are the Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra and the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra. English translations, respectively {Cleary, #205585}, and {Red Pine, 2013, #25750}. Yogācāra thought is exemplified in the works attributed to the Indian sages Asaṅga and Vasubandhu, c. 4th century CE. For references to Arnau’s work on Vasubandhu, see supra. For an informative collection of essays on the relationship between Yogācāra and Madhyamaka thought, see {Garfield and Westerhoff, 2015, #222941}

[74] {Blumenthal, 2013, #236942}, 93.

[75] {Germano and Waldron, 2006, #26508}, 37-41.

[76] {Higgins, 2012, #296638}, 446.

[77] Although my reading is primarily based on Buddhist doctrines, I will also point out śaiva influences in the following summary of the story. Advaita strands have been given more scholarly attention. See, for example, Slaje’s philological research, which led him to argue that the Laghuyogavāsiṣṭha (a shorter recension, LYV) was subjected to Advaita-Vedānta redaction, {Slaje, 1998, #62219}

[78] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 346.

[79] The image of the wish-fulfilling tree (Skt. kalpavṛkṣa) is shared by various Indian spiritual traditions. It was used by the Tibetan Buddhist master Tsongkhapa to allude to the great power of compassion: {Ozawa-de Silva, 2015, #150848}, 217.

[80] Some might point to the subtle physiology of Trika Śaivism. For example, the radiance of mount Meru is compared to the “lustre of a yogi” who has ‘opened’ through yoga a psychic portal at the crown of the head, the upper end of suṣumnā nāḍī (the central channel of the subtle body in many models of yogic physiology), {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370} 346. Timalsina also highlights an allusion to the fire of kuṇḍalinī that is not evident in Swami Venkatesananda’s rendition: “the flames of the fire from the crater of this mountain appears as if the jāṭhara fire that has surged up to the head” (chap.14.18),” {Timalsina, 2011, #57349}, 306. A connection is drawn here between the macrocosmos (mount Meru) and the microcosmos of the body (merudaṇḍa being the spine of the body).

[81] References to these birds might serve a symbolic function, since the word vehicle (Skt. yāna) is often used in the sense of a spiritual path.

[82] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 346.

[83] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 347.

[84] For an introduction to Śaivism, see {Sanderson, 2009, #180970}

[85] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 349.

[86] Timalsina explains that the conception represents a Tantric Kulayāga ritual, in which the union of Yoginīs and Vīras makes possible a noble birth (305). A Śaiva religious background is evident in the references to the deity Hara, “god of gods (…) devoted to the welfare of the entire universe”, whose consort occupies half of his body (347-8). This figure and its retinue display the non-dual symbolism of Śiva-Śakti, both antinomian and transformative. Regarding the affiliation of the female deities, Hanneder points out a difference between the YV, the Kashmiri version (Mokṣopāya), and the LYV. The Mokṣopāya alludes to the right and left streams of Śaiva tradition, represented by the two groups of fearsome female “mothers” who are connected to the deities Bhairava and Tumburu, respectively (Hanneder, 74). These two groups assemble to worship together in the Mokṣopāya, mirroring a fusion of the two streams of Śaivism that “makes sense only within a very specific doctrinal context, that is within the Kashmirian non-dualist cults” (Hanneder, 73).

[87] {Timalsina, 2011, #57349}, 306. On Śaiva tantric traditions and social integration, see {Sanderson, 2009, #180970}, 284-301.

[88] {Timalsina, 2011, #57349}, 306.

[89] On emptiness in tantric or esoteric Indian Buddhism, see {Davidson, 2002, #83960}, 100-2. On non-duality and notions of purity and impurity, {Snellgrove, 2004, #55806}, 160-70. On the ethical implications, see supra.

[90] On modalities of reification and the notion of vāsanā (mental conditioning or impulses) in Yogācāra, see supra.

[91] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 350.

[92] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 350.

[93] Constraints of space prevent me from discussing these elemental dhāraṇās further; for an extensive discussion, see {Chapple, 2020, #134240}. For a discussion of the five great elements in the specific context of the YV, see {Chapple and Chakrabarti, 2015, #288311}, 267-88. Also interesting is Mingyur Rinpoche’s phenomenological description of the dissolution of the elements during a near death experience, {Rinpoche and Tworkov, 2019, #289283}, 219-28. For an interesting parallel of outer and inner landscapes in the tradition of early Christian monasticism, see {Christie, 2012, #118401}, 32-69.

[94] For a discussion of the act of creation in Indian thought as “both as a cosmogonic myth and as a symbol of creative power in a person”, see {Chapple, 1986, #30416}, 14. Campagna elaborates on the notion of apocalypse in connection to individual and collective forms of worlding: “When the voice that sings ‘the world’ starts to fade out, the range of possibilities that made up its future also begins to evaporate. The end of a world is an apocalypse that reveals (apokalyptein) the nature of time, at the same moment in which it slaughters it.”{Campagna, 2021, #258711}, 18.

[95] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 353.

[96] I borrow the expression from a collaborative tome on the YV, {Chapple and Chakrabarti, 2015, #288311}, 95.

[97] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 350. The resemblance to Nāgārjuna’s dialectics and its rejection of inherent existence is evident, see supra.

[98] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 350. See Campagna’s discussion of aesthetics and metaphysics: “The act of foundation of the world – the fiat lux that brings a world out of the onslaught of raw perceptions – is not only the main aesthetic act, but also the most frequent. Repeated at each instant, it remains axiomatic in every distinction between things, subjects and landscapes. The process of worlding brings the subject to the immediate proximity of their own perceptions (aisthetika), and it allows them to reshape their landscape through intuition alone” {Campagna, 2021, #258711}, 58.

[99] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 351.

[100] Inspired by anarchist thinker Ernst Jünger, who spoke of stereoskopischen Wahrnehmung (‘stereoscopic perception’). In his “Sicilian Letter to the Man in the Moon” (Sizilischer Brief an den Mann im Mond), Jünger poetically illustrates the possibility of transcending a metaphysical Either/Or dichotomy, by seeing like children a face on the moon, without renouncing scientific ‘adult’ knowledge. For a discussion of this notion as a form of ‘grotesque’ worlding, see {Campagna, 2021, #258711}, 116.

[101] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 353-4.

[102] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 354.

[103] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 354. On non-dual wisdom and ethics, see supra.

[104] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 355-8. Timalsina explains that Advaita influence in the YV has often eclipsed the presence of Tantric and haṭhayoga elements (304). Bhuśuṇḍa’s tale is an exception, since it “places the yoga of breathing in the same status as the contemplative techniques generally addressed as jñāna or jñānayoga.” (Timalsina, 304). The possible compilatory nature of the YV may account for the contrast between the practice advocated by Bhuśuṇḍa and the more frequent emphasis on sudden realization of the illusory nature of reality (Timalsina, 303).

[105] Singh explains that the term prāṇa is used in three senses in Śaivism: (i) As life-force (prāṇa-śakti); (ii) in the sense of a specific biological function; (iii) as a reference to breath {Singh and Muller-Ortega, 1991, #209647}, xxxi.

[106] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 355.

[107] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 358. Another concept used in the explanation is dvādaśāntam, explained by Swami Venkatesananda as “a magnetic field around the body twelve finger-widths all round,” which is also composed of prāṇa-apāna, {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 356n. The use of such terms in the tale and the allusion to elemental dhāraṇās could be evidence of Tantric influence, {Timalsina, 2011, #57349}, 317-319. Timalsina has suggested a connection between Bhuśuṇḍa’s practice and verses 17.2-10ab of the Śaiva Mālinīvijayottara tantra, {Timalsina, 2011, #57349}, 317.

[108] {Muller-Ortega, 1991, #272894}, xv. Very similar practices are found in the Śaiva Vijñāna-bhairava tantra. This text emphasizes direct experience of the non-dual, ultimate reality, and one of the themes reflected in its methods is the space or interval (Skt. madhya), {Singh, 1991, #209647}, xxxix-xl.

[109] Similarly, Douglas Christie argues that the practice of prosoche (‘attention’) from the ancient Christian contemplative tradition “can help us heal some of the imaginative rifts that have prevented us from seeing and living in the world with a sense of its integrity, beauty, and mystery” {Christie, 2012, #118401}, 141-79.

[110] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 356. For a discussion of the jīvanmukti state in the YV, see {Fort, 2015, #98098}. For a discussion in the LYV, see {Slaje, 2000, #275461}

[111] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 358. See Chapple’s explanation of the detachment from the fruit of one’s actions advocated in the YV: “[Vasiṣṭha] urges Rāma to transcend the realm of desire and change through performing his required tasks with zeal, working for the benefit of all his subjects. (…) one attains an equanimity that sanctifies the nature and content of one’s actions, setting an example for others. It also provides a working model for the adoption of a tolerant point of view, essential for the maintenance of harmony in a social setting characterized by diversity.” {Chapple, 1986, #30416}, 10-11. For the Sanskrit and an English translation of teachings on the yoga of action (Skt. karma yoga) in the Bhagavad Gītā, see {Chapple, 2009, #57867}, 158-200.

[112] For a discussion of these practices in Buddhism and Patañjali’s Yogasūtra (including the Sanskrit and English translation of verses I:33, III:23), and an interesting analysis of the Sanskrit feminine gender, see {Chapple, 2008, #126695}, 63, 72-4, 119, 190, 244-5.

[113] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 359.

[114] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 362.

[115] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 363. Also: “In fact, even the Creator is but a notion in the cosmic mind; the world-appearance, too, is a notion in the mind. These notions gain strength in the mind by being invested repeatedly with the mantle of truth and, therefore, they arise again, and again, creating the illusory world-appearance with them” (361).

[116] {Venkatesananda, 1993, #241370}, 365.

[117] I borrow the expression from {Lakoff and Johnson, 2003, #231558}

[118] For an overview of some issues and sources, {Pedersen and Brincker, 2021, #12534}

[119] On negative social and ecological externalities of global capitalism, see {Giuliani, 2018, #14064}

[120] On the role of reactionary populism in the political sphere, see {Faber, 2018, #203148}

[121] Interesting parallels could be drawn to the early Christian monastic practices of ‘place-making,’ see {Christie, 2012, #118401}, 102-141.

[122] On reading, creative imagination and moral development in the YV, see {Chapple and Chakrabarti, 2015, #288311}, 189-218. This also brings to mind Pierre Hadot’s exercises spirituels (‘spiritual exercises’). See, in particular, apprendre à lire, and la physique comme exercice spirituel, {Hadot, 2002, #55221}, 60-74, 145-64. English translations of Hadot’s ideas (not necessarily the same texts), are present in the sections on method, the figure of Marcus Aurelius, and “The view from above” in {Hadot, 1995, #50743}, 47-78, 179-205, 238-50.

[123] On the bodhisattva ideal, see supra. Chapple’s explanation is clear: “The ethic of the YV requires a refined, purified psychological state, carefully cultivated through effort (yatna) and creativity (pauruṣa). (…) By clearing one’s psyche and body of the cobwebs of the past, one attains a clarity that brings one a place of immediate sensory perception. Without expectation of the future or reliance on the past, the liberated person is able to act freely and set an example for others” {Chapple and Chakrabarti, 2015, #288311}, 186.

[124] On apocalypse and worlding, see supra. Space limitations prevent me from further exploring Campagna’s insightful discussions on apocalypse, prophetic culture as a worlding of solidarity with post-future subjects, and apocatastasis. See {Campagna, 2021, #258711}, 15-20, 80-91, 147-65.